Poverty

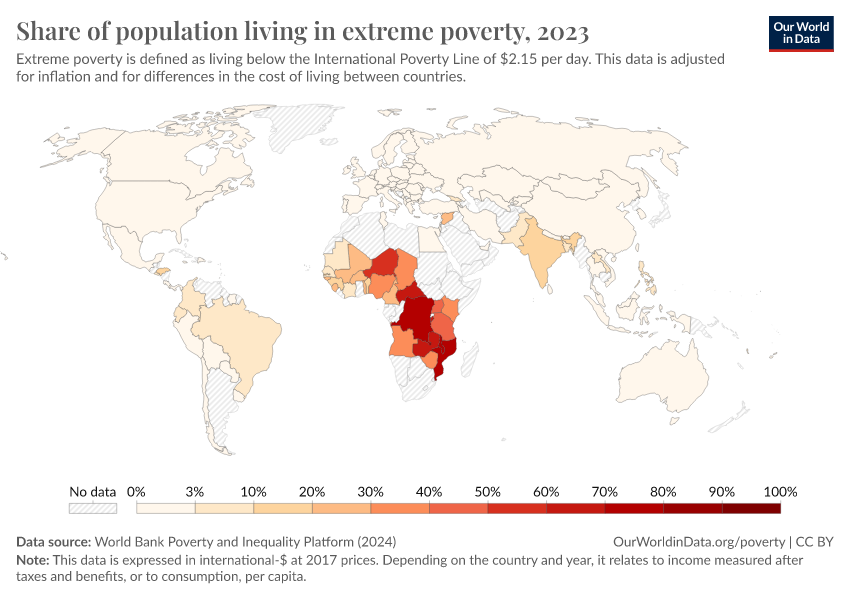

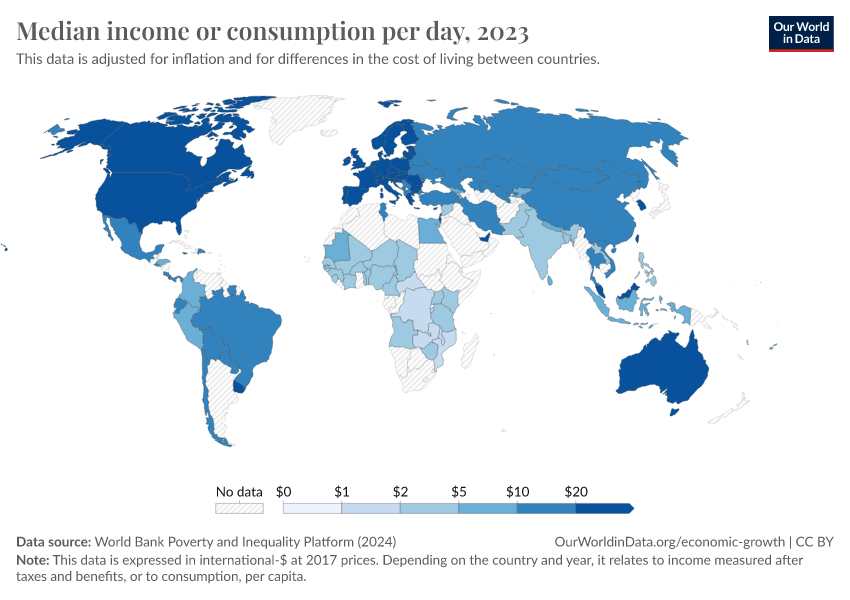

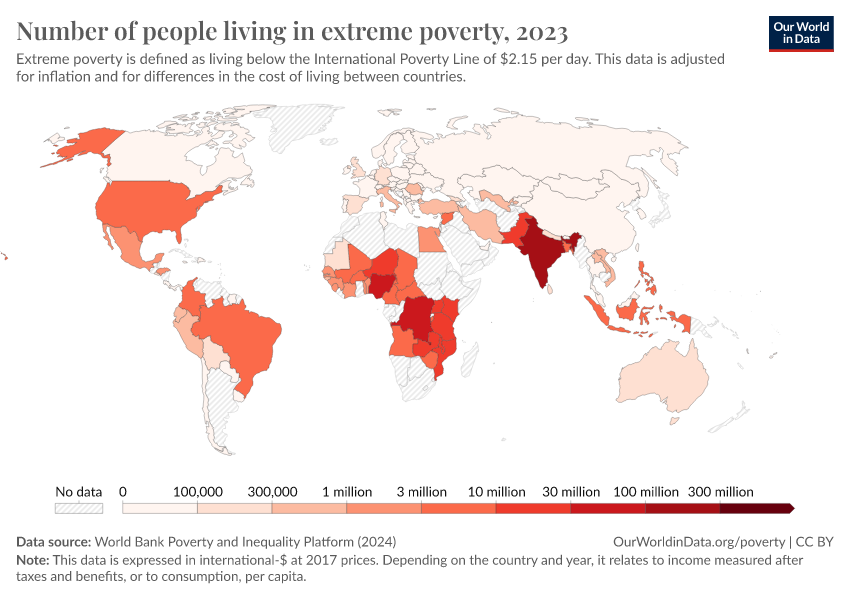

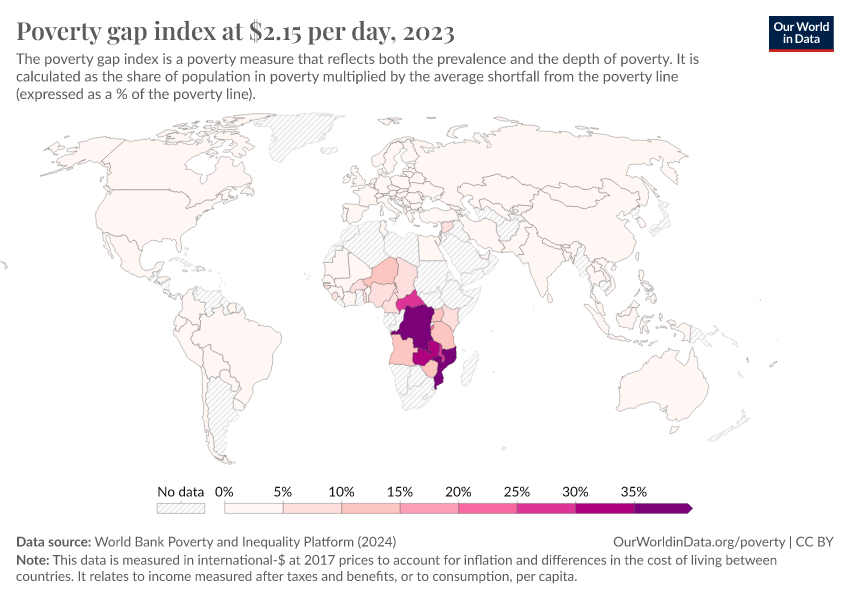

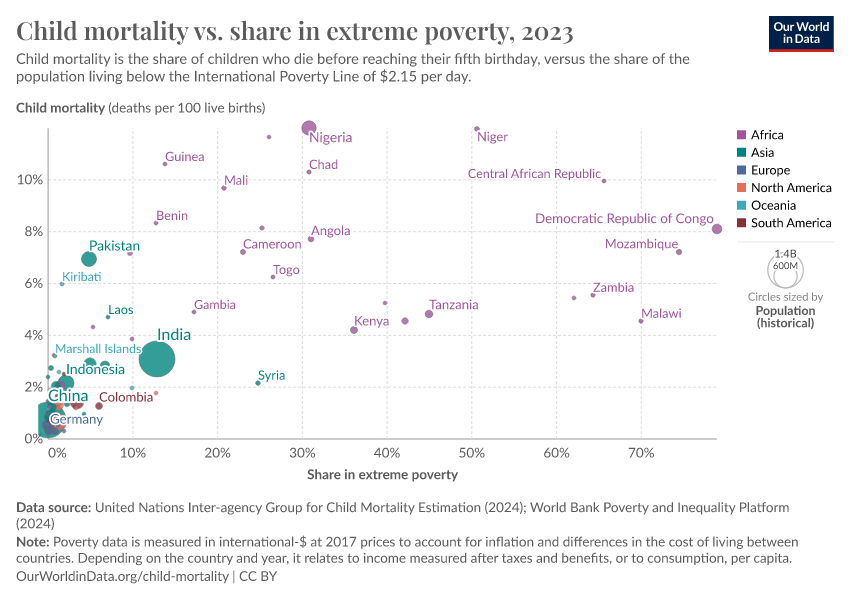

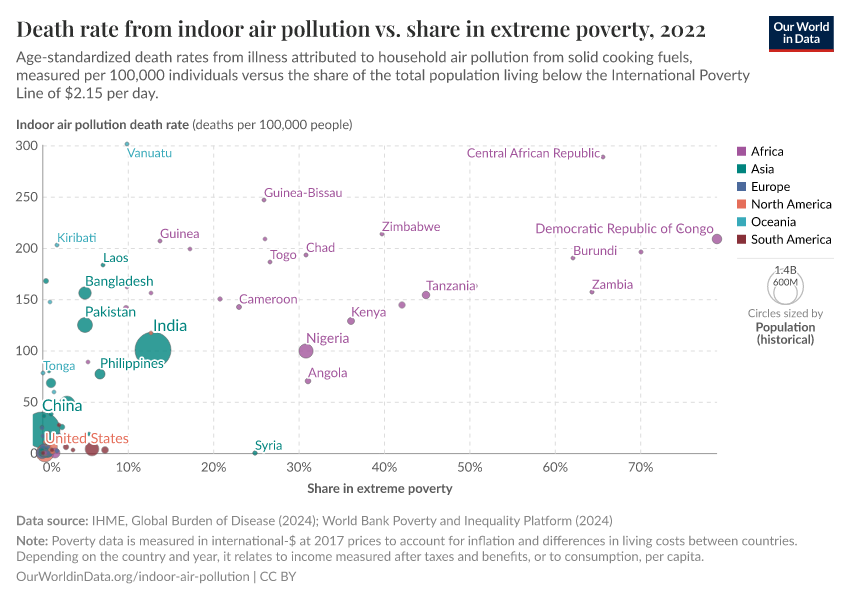

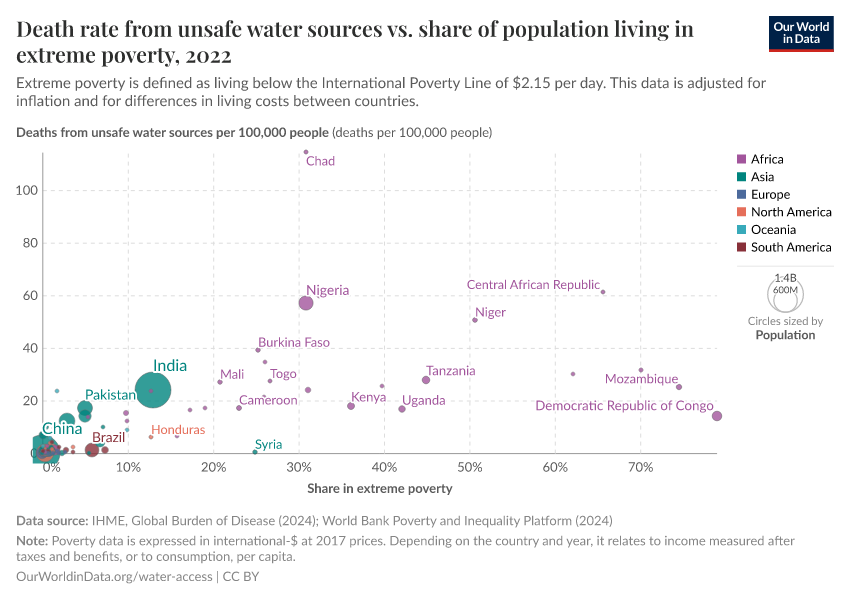

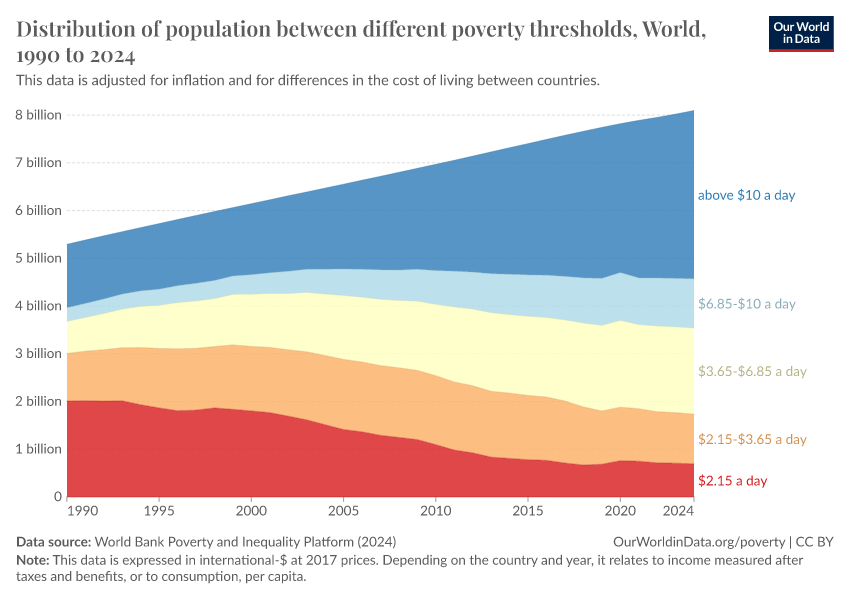

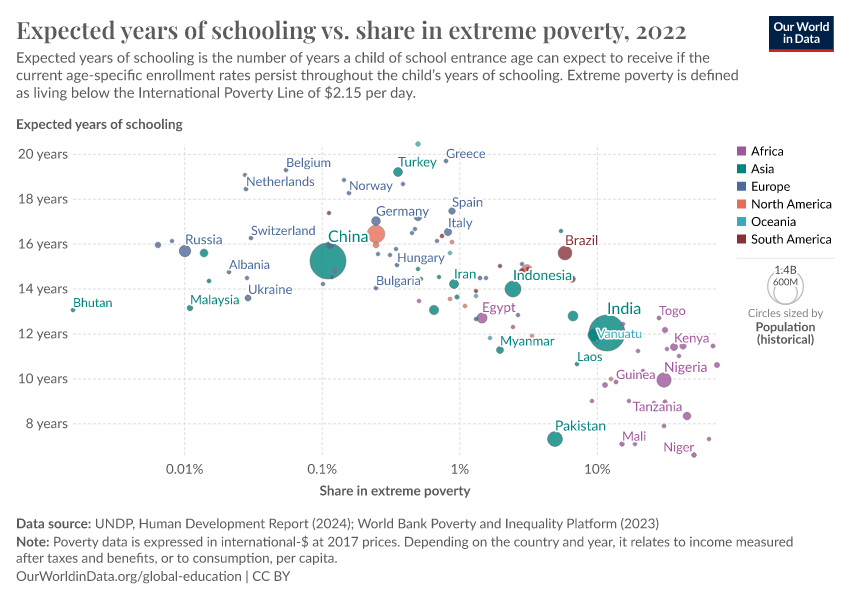

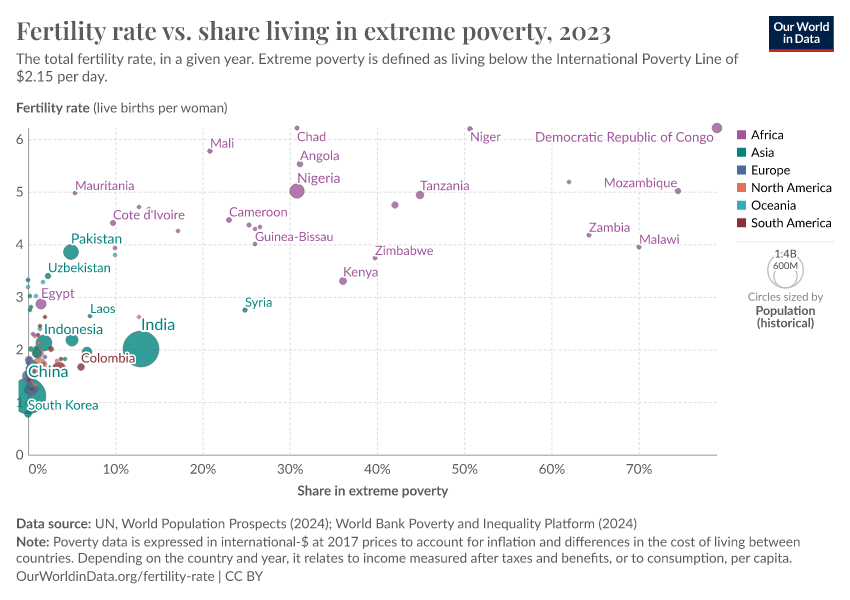

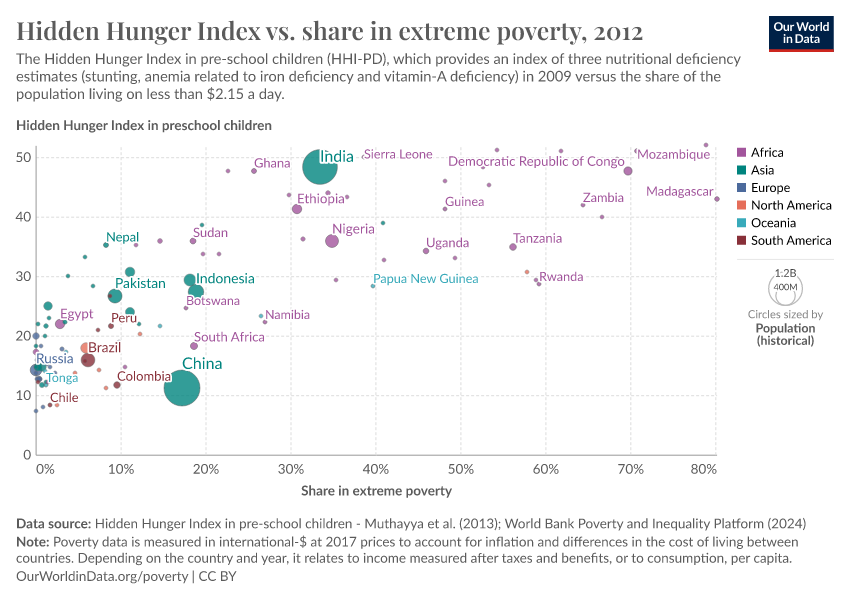

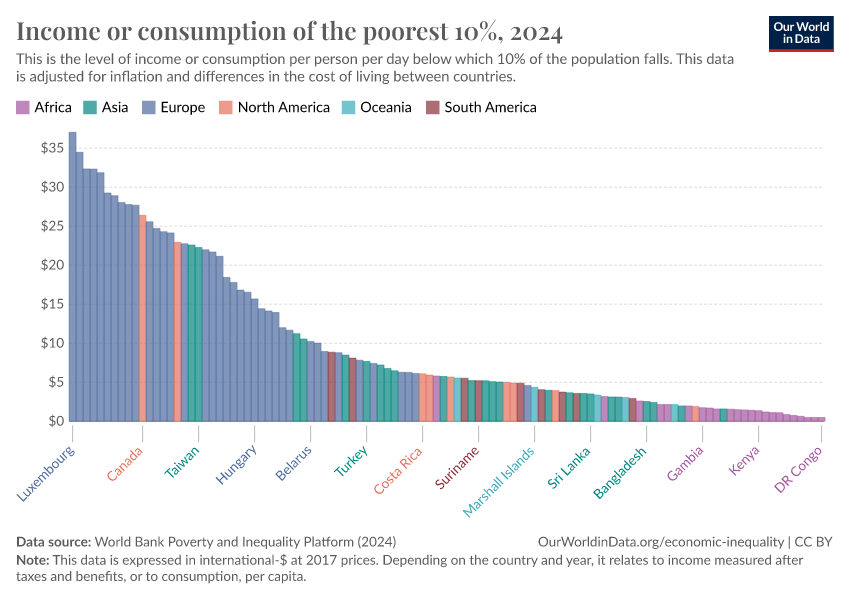

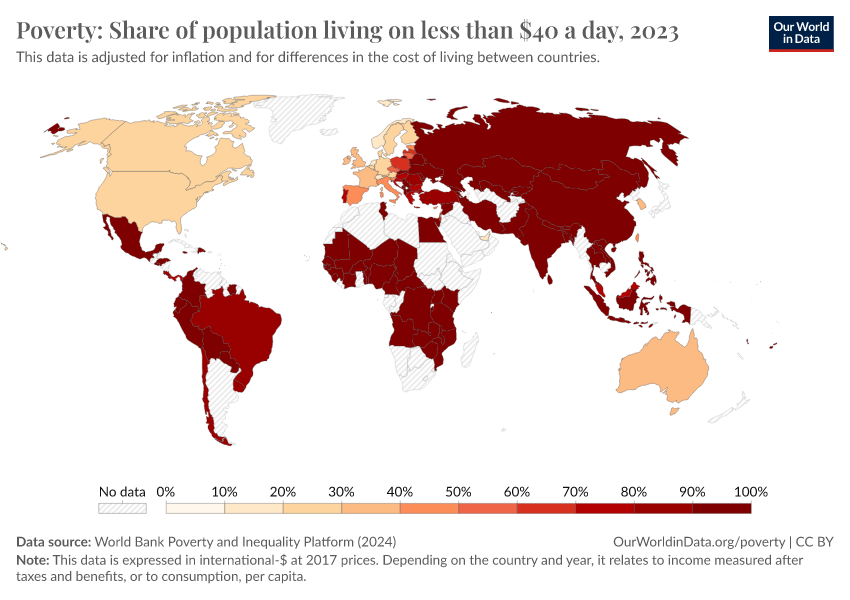

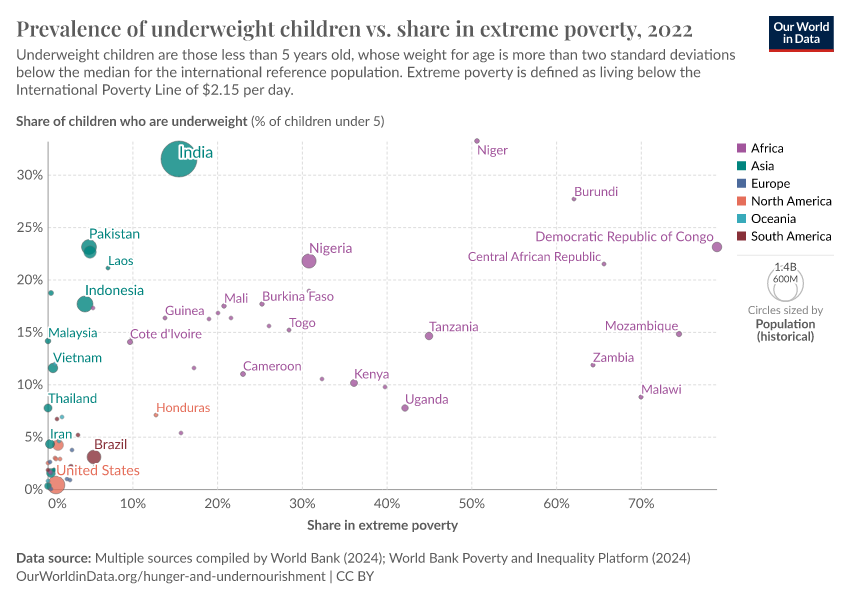

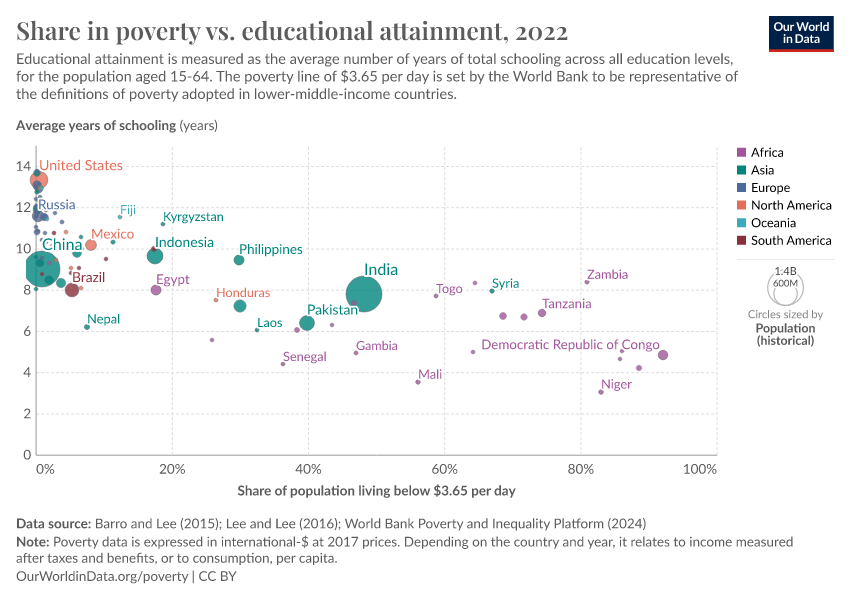

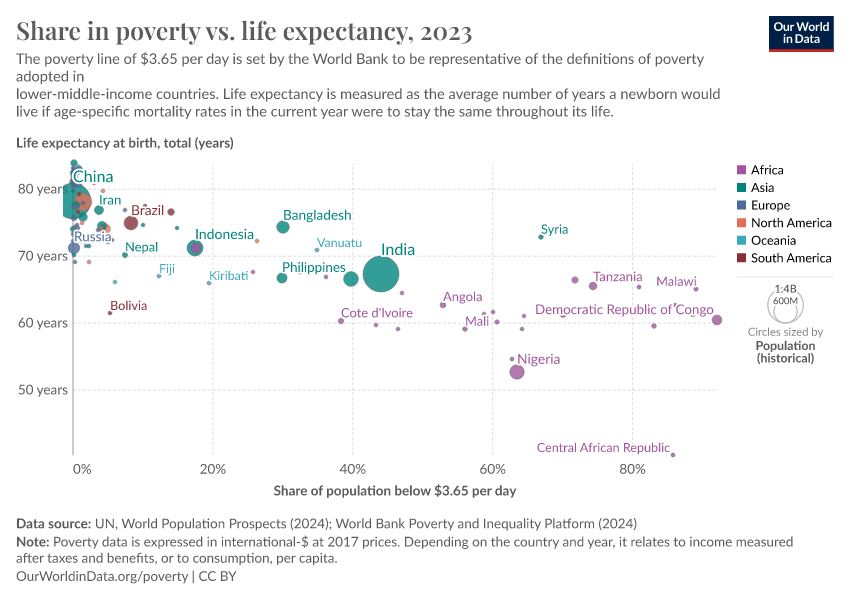

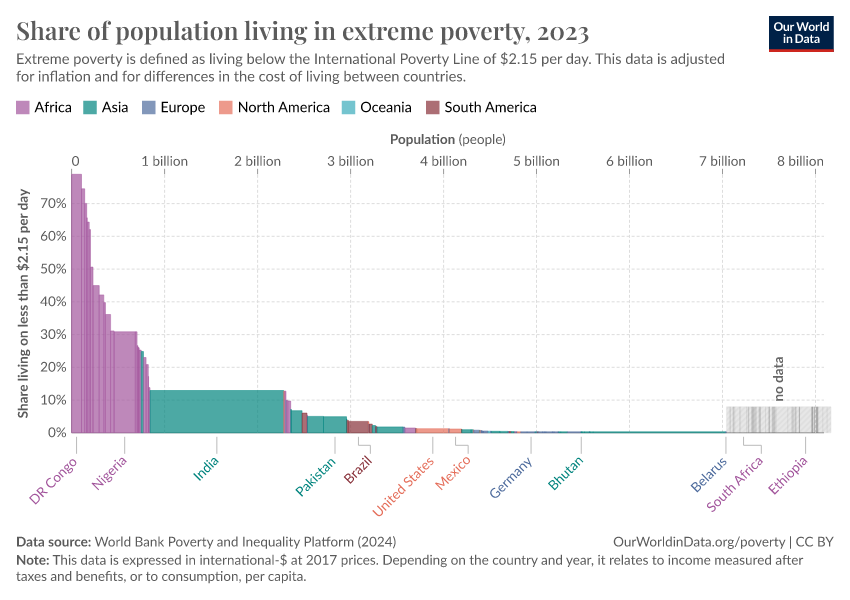

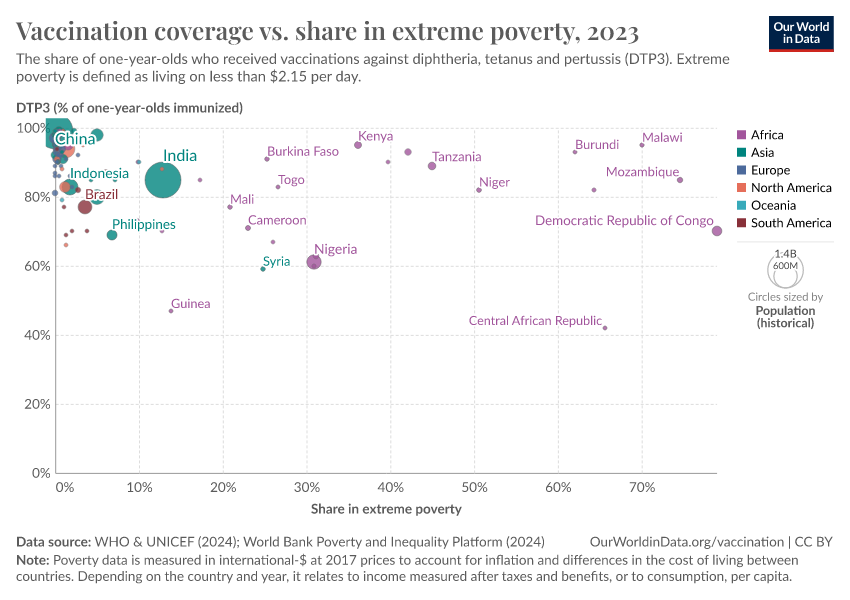

Global poverty is one of the most pressing problems that the world faces today. The poorest in the world are often undernourished and without access to basic services such as electricity and safe drinking water; they have less access to education and suffer from much poorer health.

In order to make progress against such poverty in the future, we need to understand poverty around the world today and how it has changed.

On this page you can find all our data, visualizations and writing relating to poverty. This work aims to help you understand the scale of the problem today; where progress has been achieved and where it has not; what can be done to make progress against poverty in the future; and the methods behind the data on which this knowledge is based.

Research & Writing

Extreme poverty: how far have we come, how far do we still have to go?

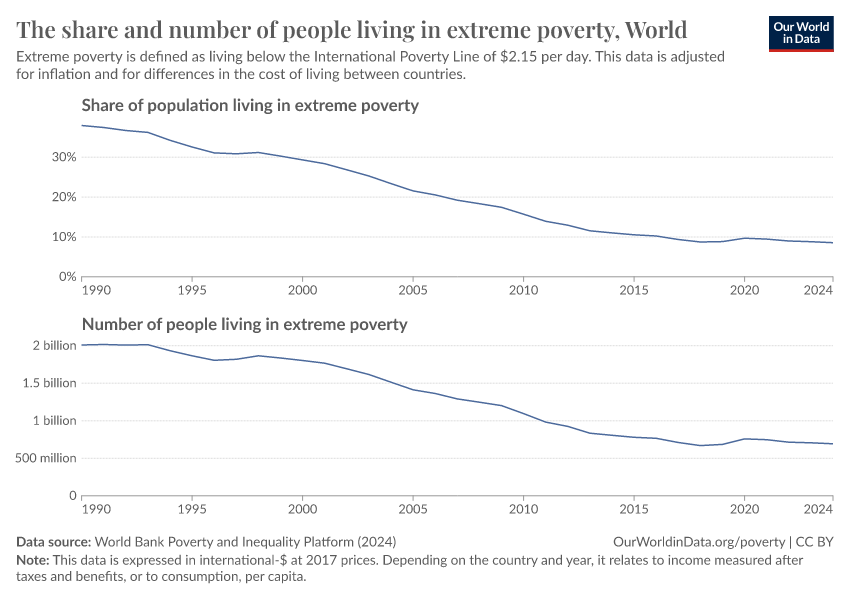

Despite making immense progress against extreme poverty, it is still the reality for every tenth person in the world.

December 16, 2024

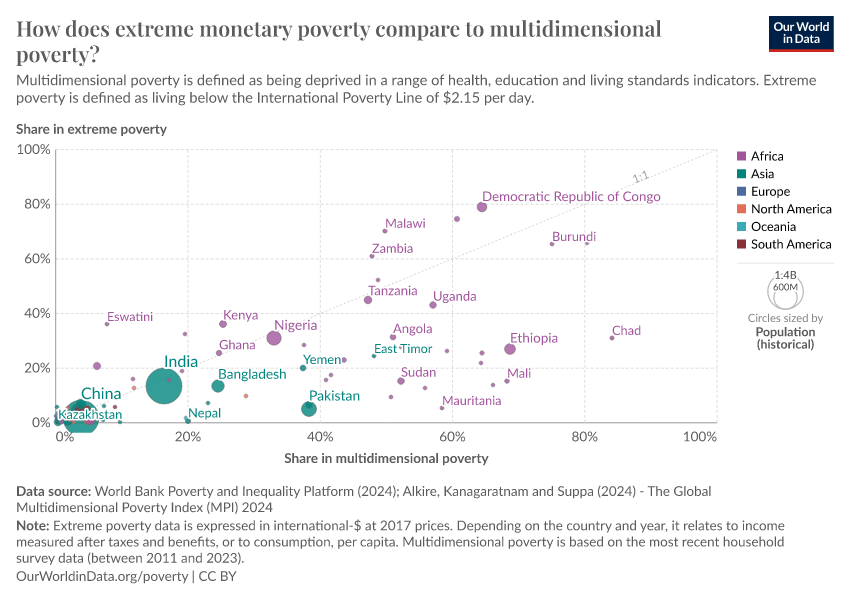

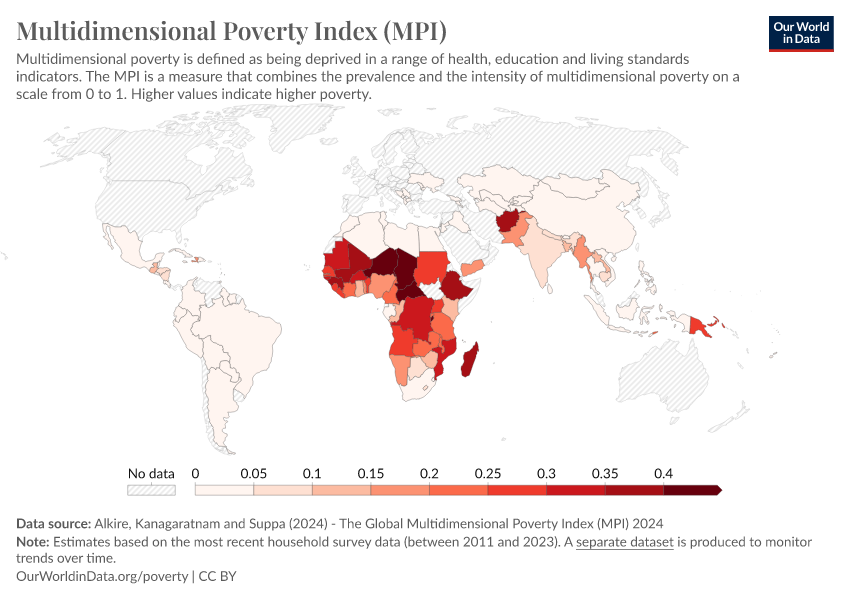

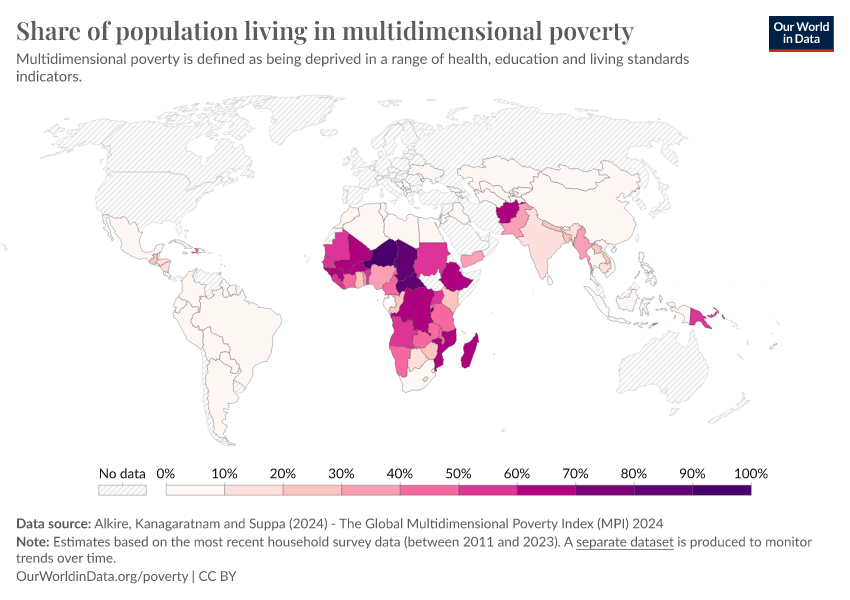

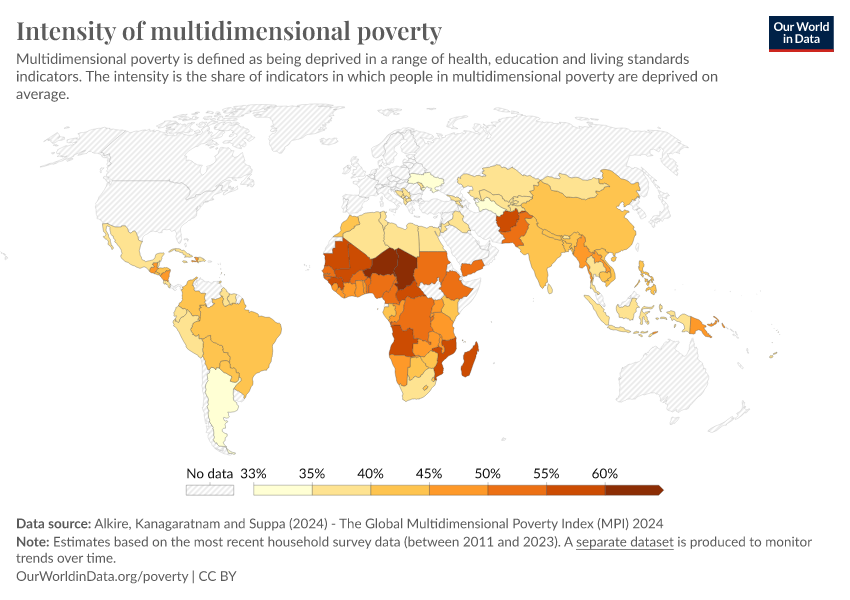

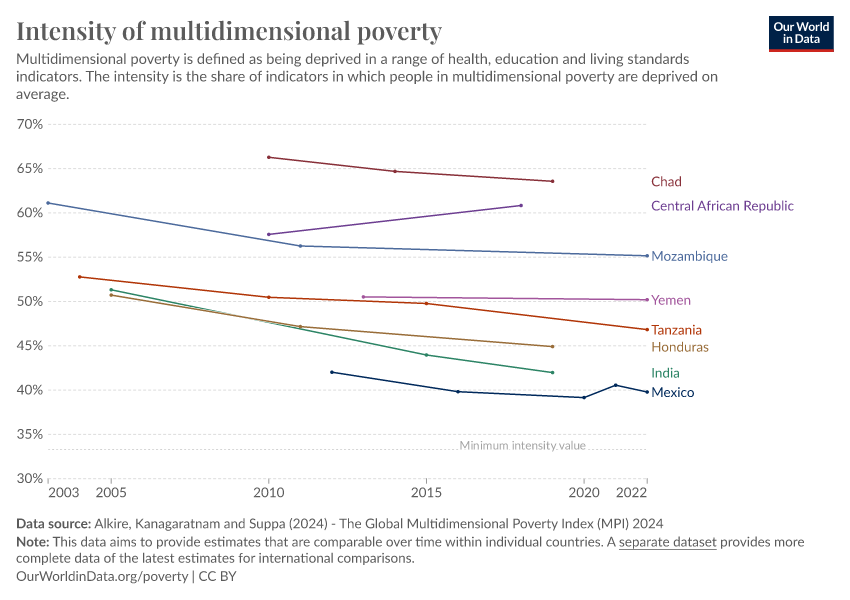

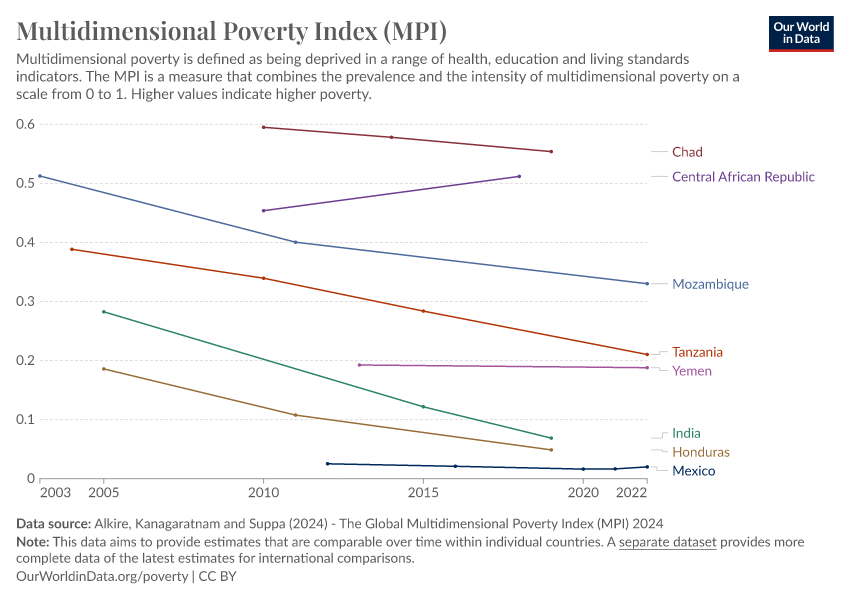

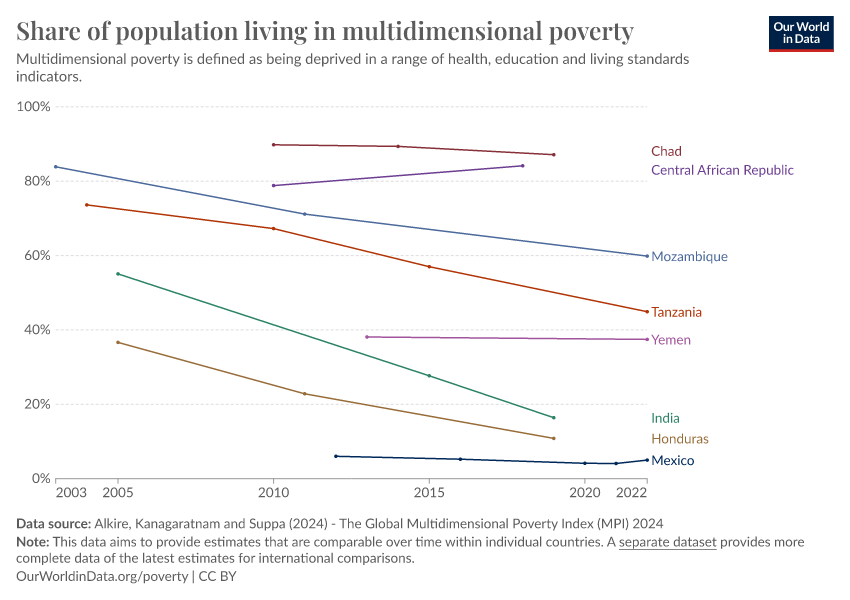

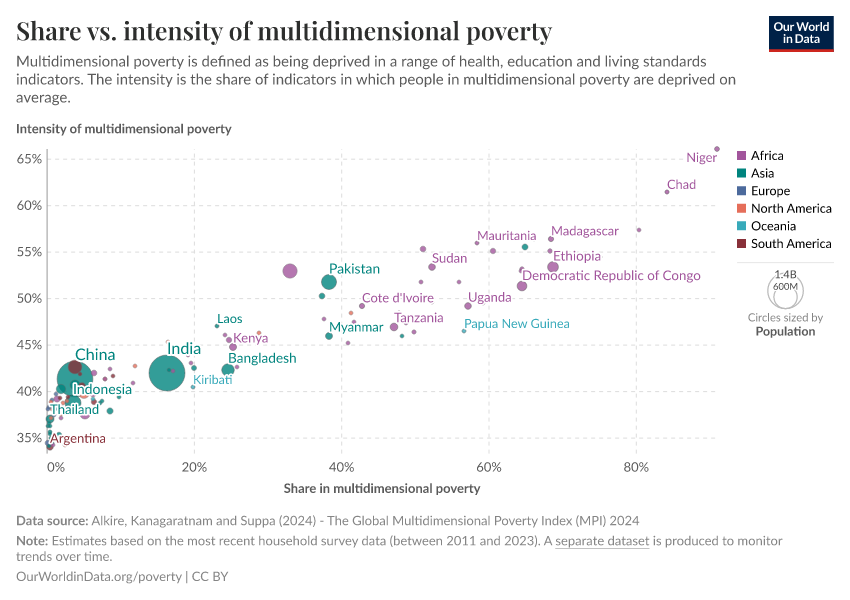

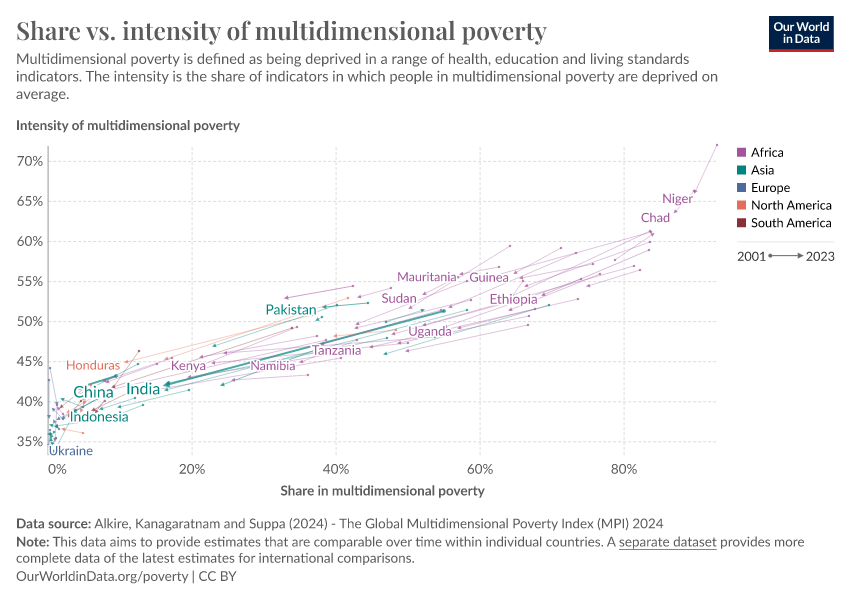

Beyond income: understanding poverty through the Multidimensional Poverty Index

The experience of poverty goes beyond a very low income. What is the Multidimensional Poverty Index, and how does it capture the diverse ways people experience deprivation?

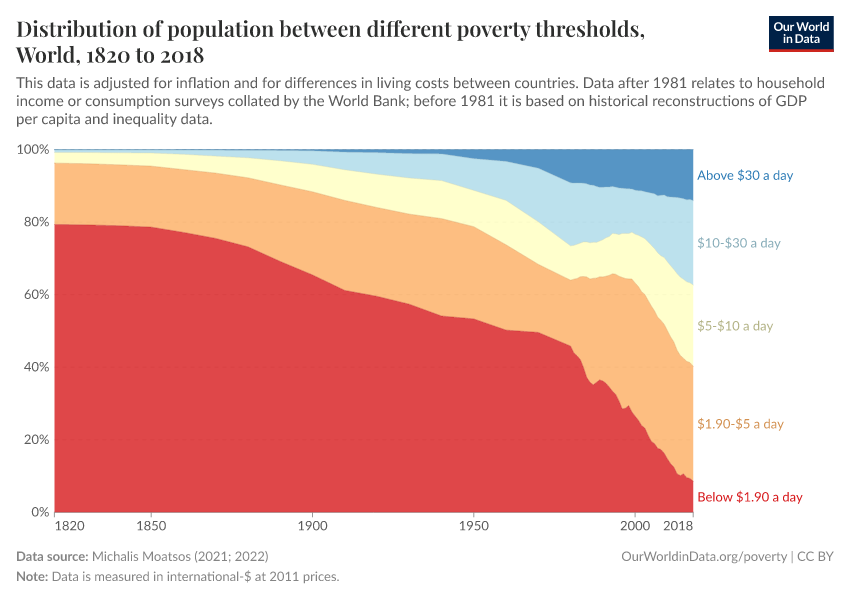

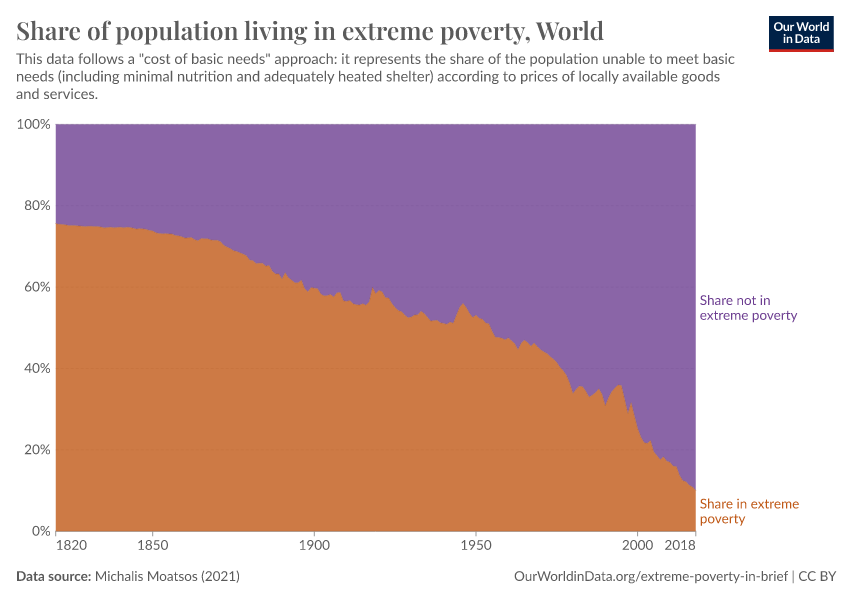

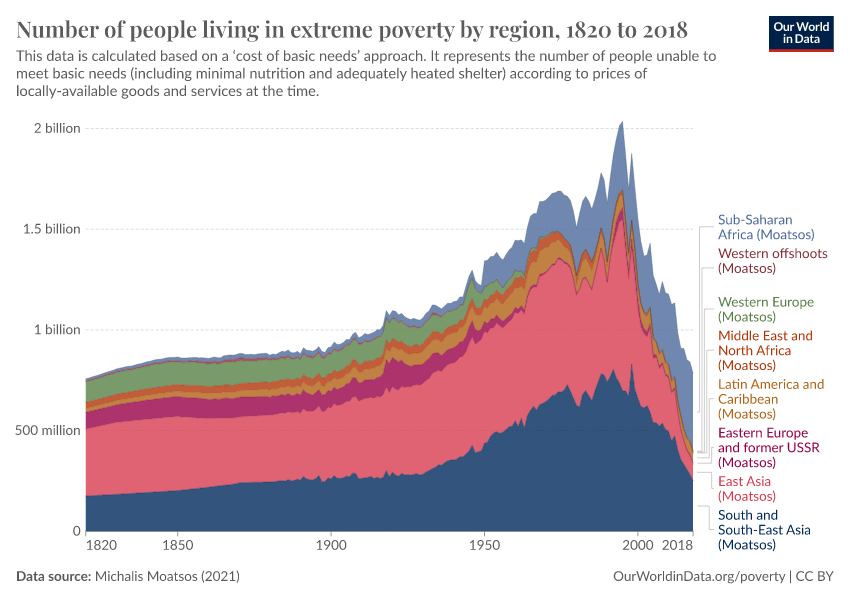

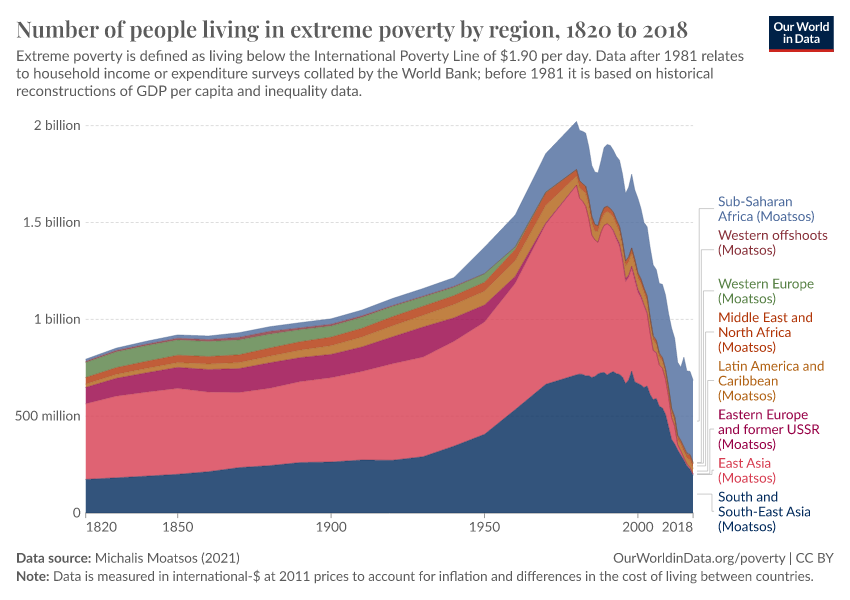

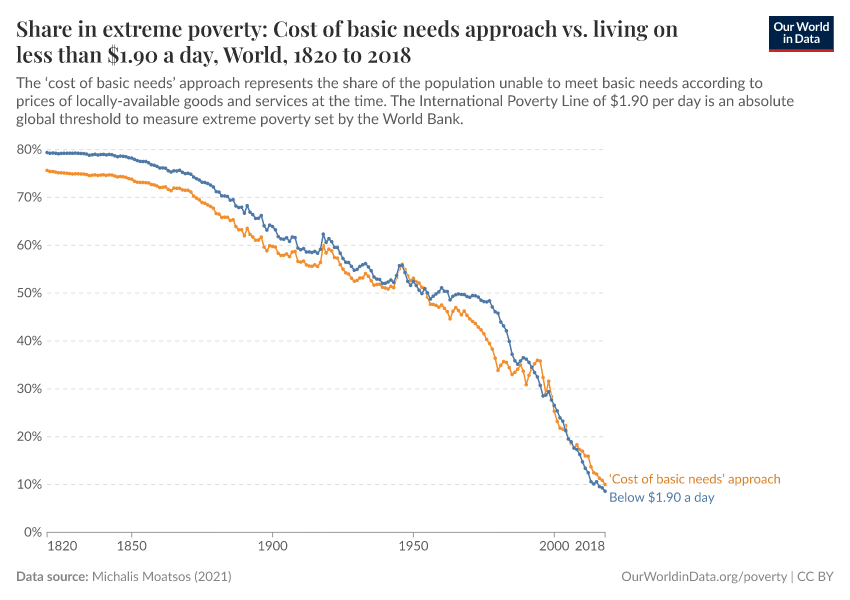

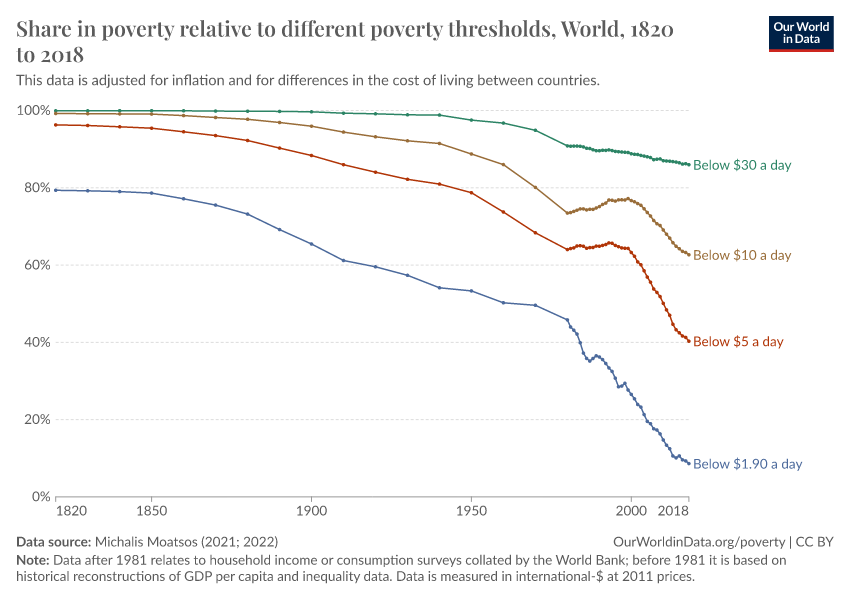

Global poverty over the long-run

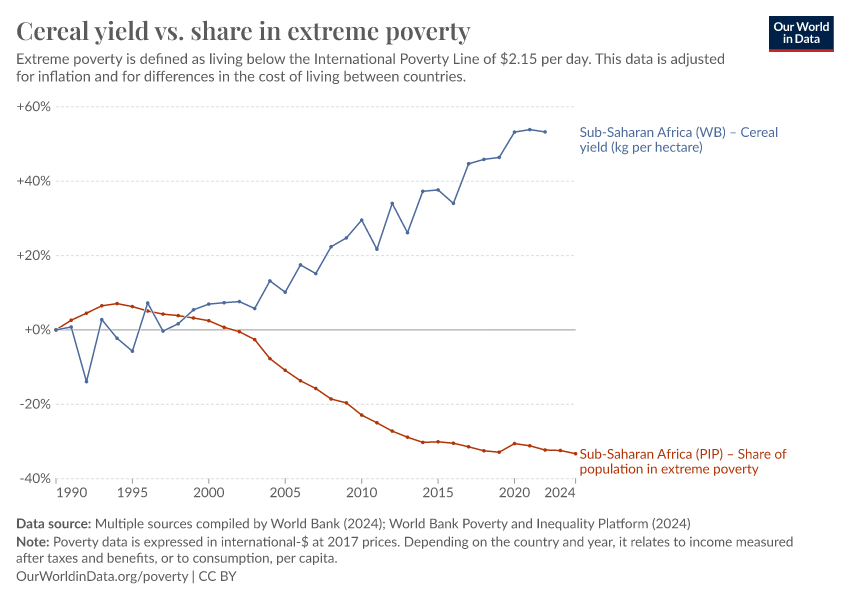

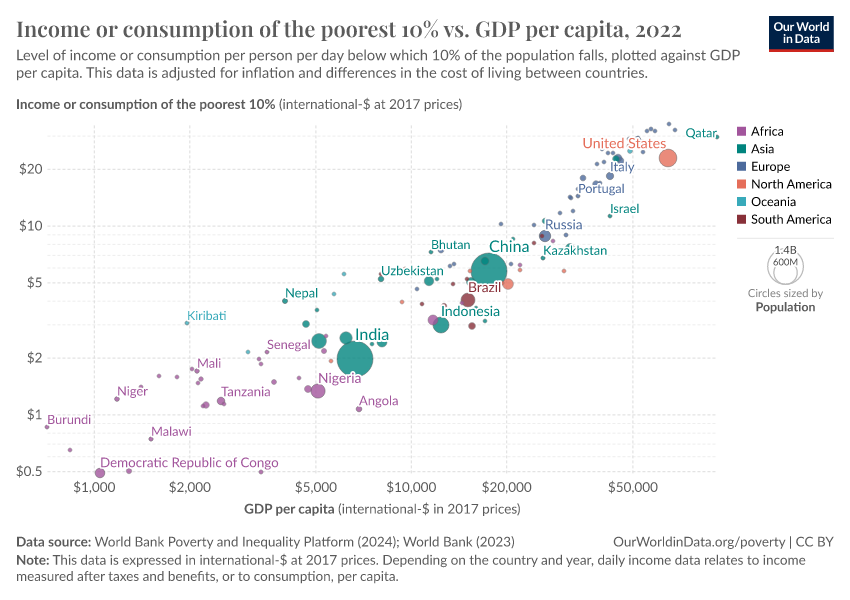

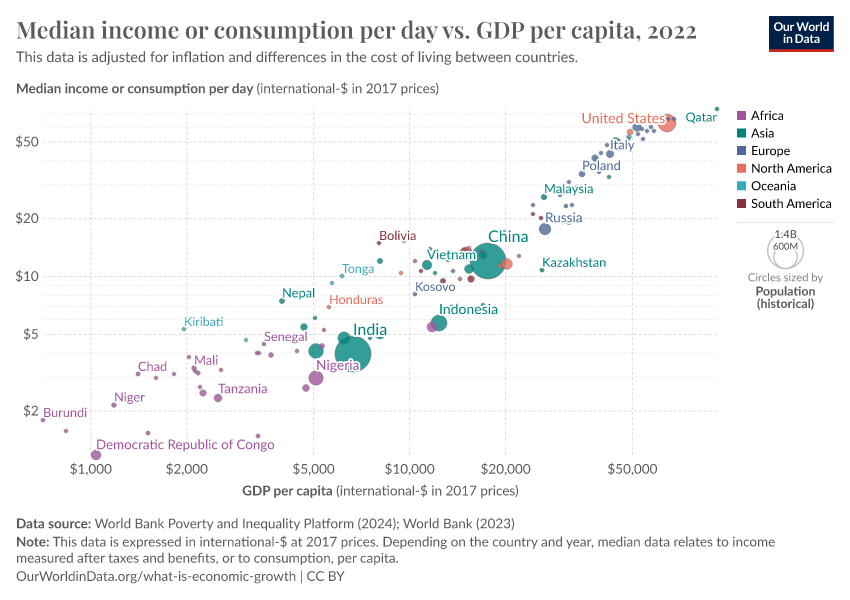

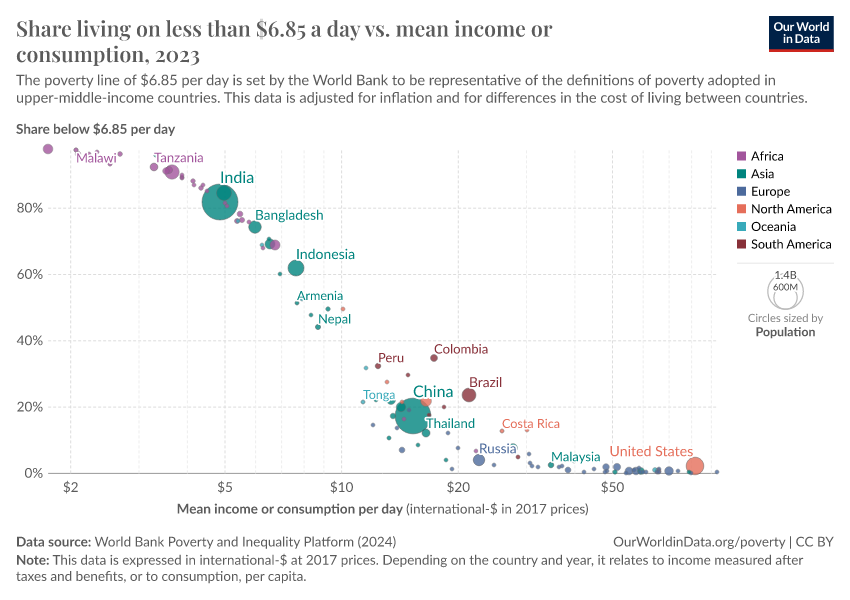

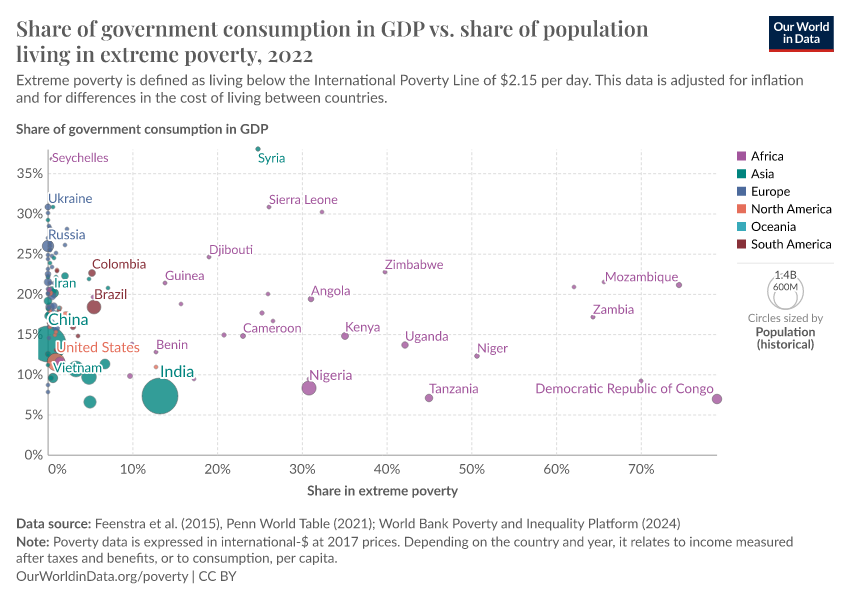

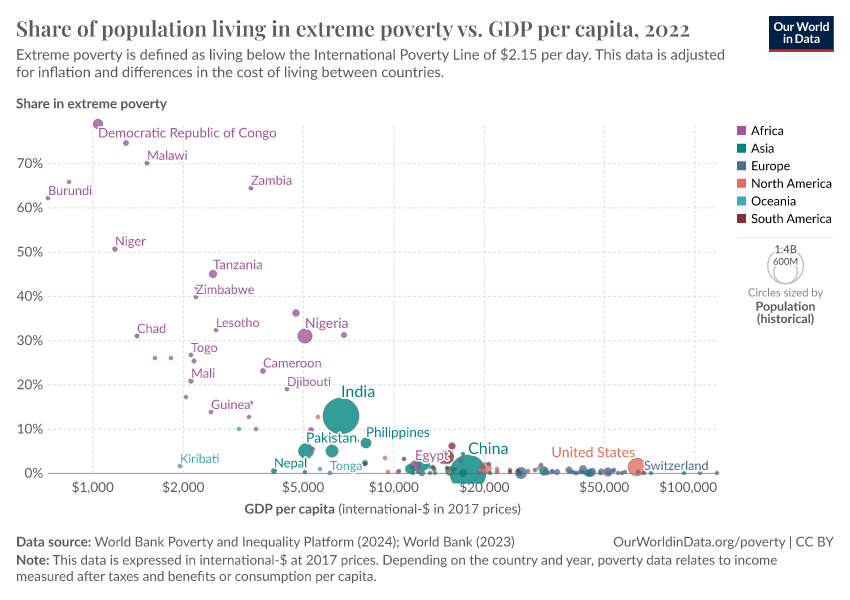

Poverty & Economic Growth

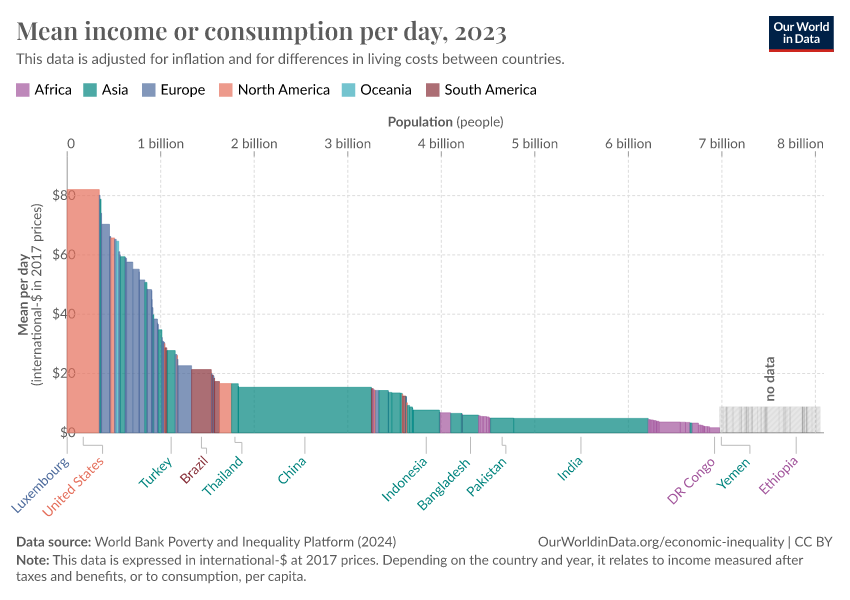

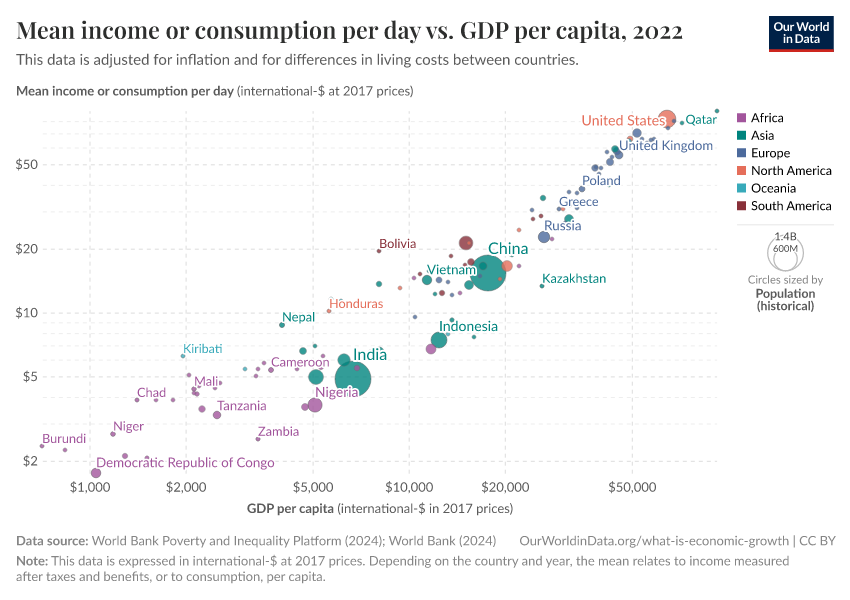

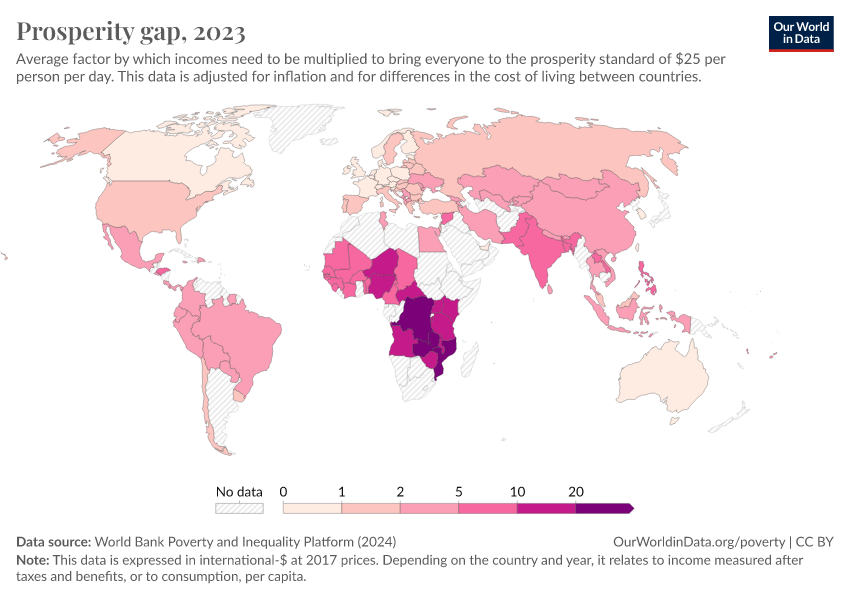

The economies that are home to the poorest billions of people need to grow if we want global poverty to decline substantially

How much economic growth is necessary to reduce global poverty substantially?

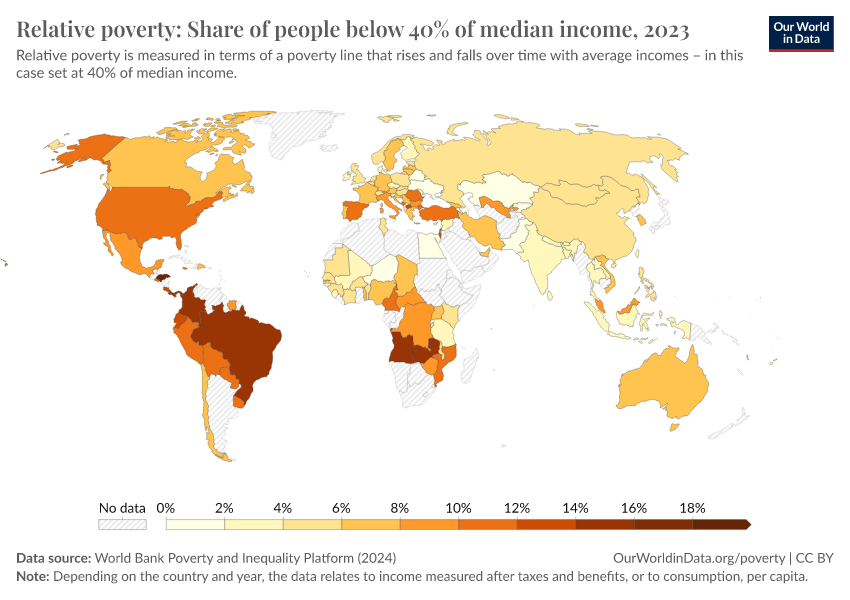

Global poverty in an unequal world: Who is considered poor in a rich country? And what does this mean for our understanding of global poverty?

What do poor people think about poverty?

Key Charts on Poverty

See all charts on this topicEndnotes

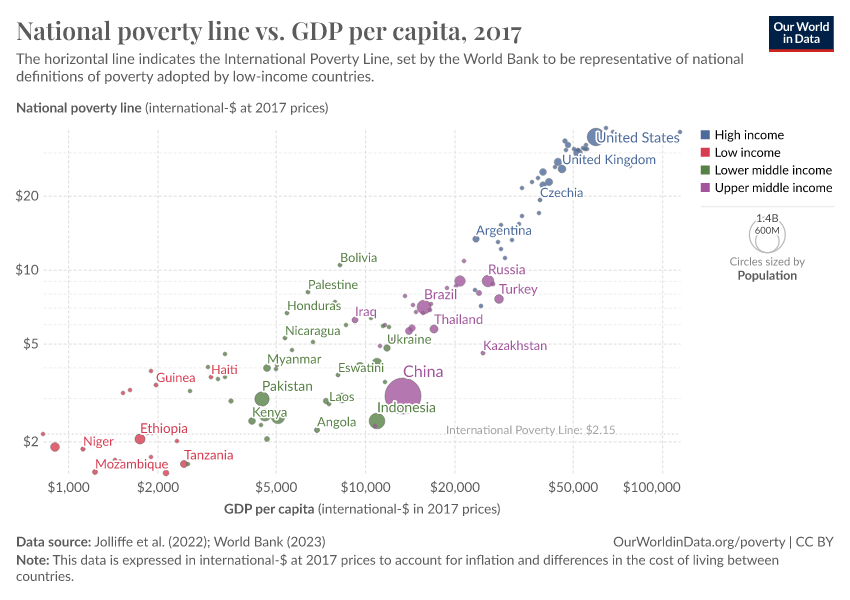

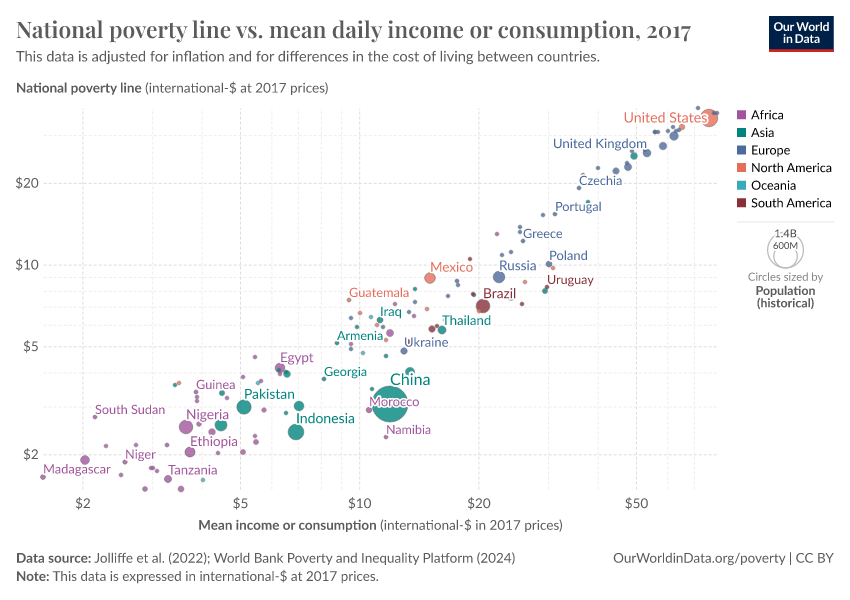

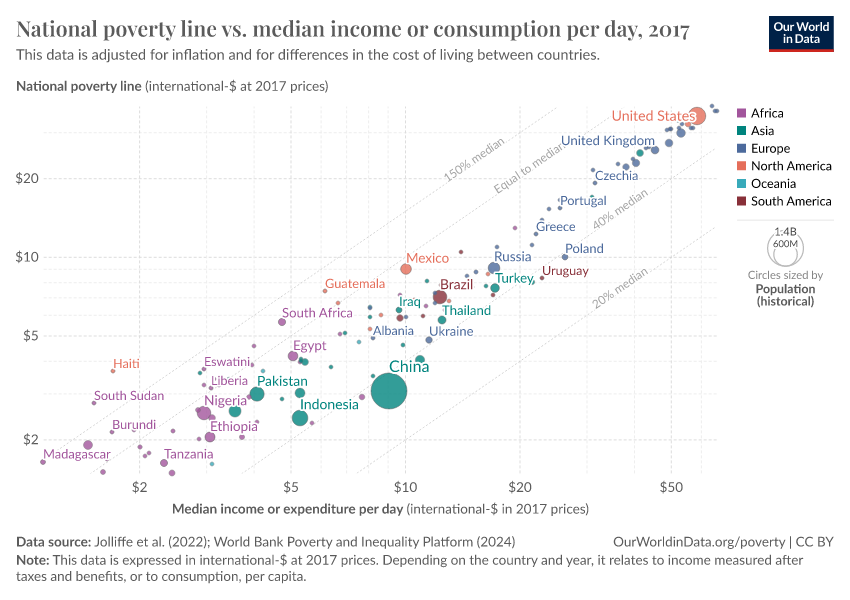

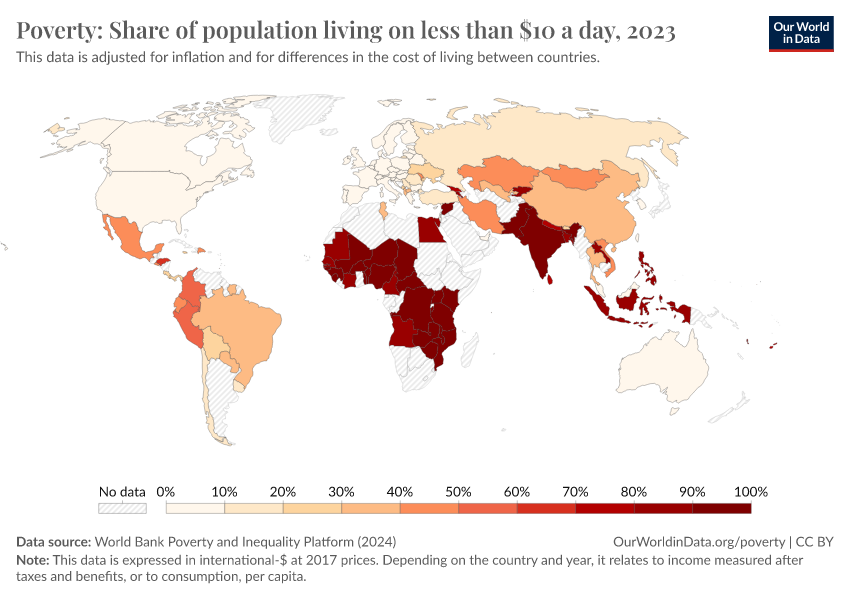

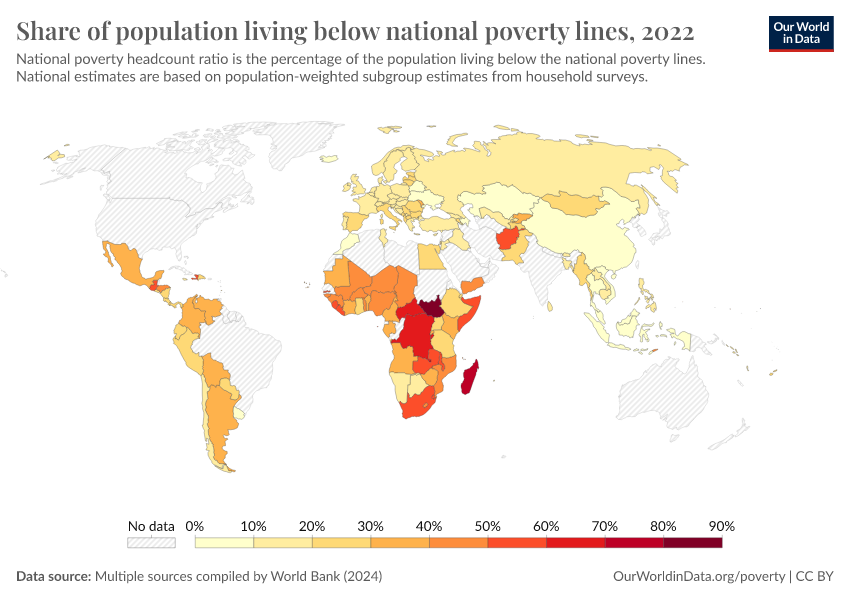

Official definitions of poverty vary across countries and are often not directly comparable due to the different ways in which poverty is measured. For example, some countries measure it using household income, others use consumption, and there are differences in how they account for the size of households.

The poverty lines shown here are an approximation of those national definitions. To make comparisons possible, the World Bank built a database of harmonized national poverty lines. For all countries apart from the United States, we take the harmonized poverty line.

Harmonized poverty lines are calculated as the international dollar figure, which, when applied to the World Bank’s Poverty and Inequality Platform (PIP) data, yields the same poverty rate as each country’s officially reported rate in a given year (typically around 2021 in the latest 2025 PIP data release). This approach allows us to express the national poverty lines on a common scale, telling us how much someone would need to live on (in international dollars) to be considered poor by the standards of their own country. You can read more about the methodology in Joliffe et al. (2024) and Foster et al. (2025).

For the US, Foster and colleagues use the OECD’s published poverty rate — which is measured against a relative poverty line of 50% of the median income. This yields a poverty line of around $44 (measured using 2023 survey data). But this is not the official definition of poverty adopted in the US. We calculated an alternative harmonized figure for the US national poverty using the same method as Jolliffe et al. (2024), but based instead on the official 2023 poverty rate reported by the US Census Bureau.

Jolliffe, D., Mahler, D. G., Lakner, C., Atamanov, A., & Tetteh-Baah, S. K. (2024). Poverty and Prices: Assessing the Impact of the 2017 PPPs on the International Poverty Line and Global Poverty. The World Bank Economic Review, lhae035. Available here.

Foster, E.M., Jolliffe, D., Ibarra, G.L., Lakner, C., Tetteh Baah, S.K. (2025). Global Poverty Revisited Using 2021 PPPs and New Data on Consumption. Policy Research Working Paper. World Bank, Washington, D.C. Available here.

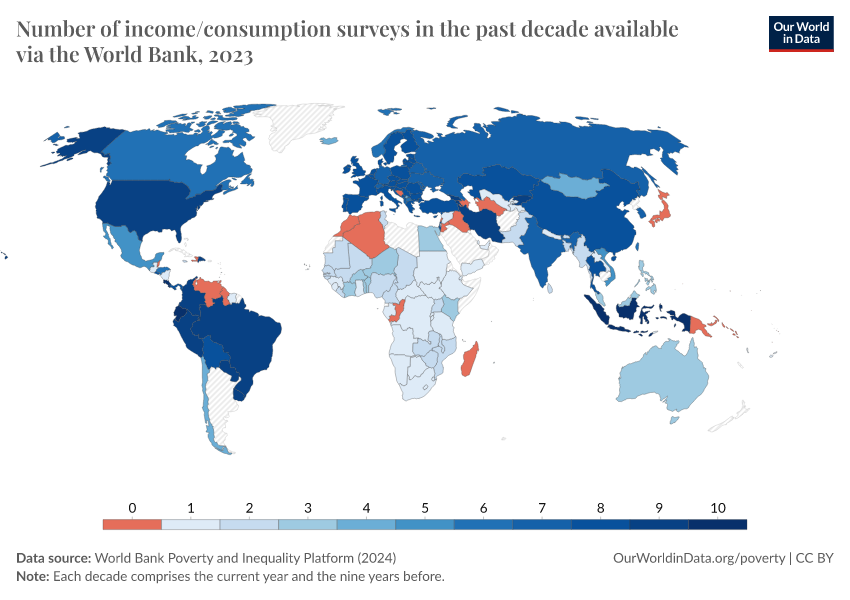

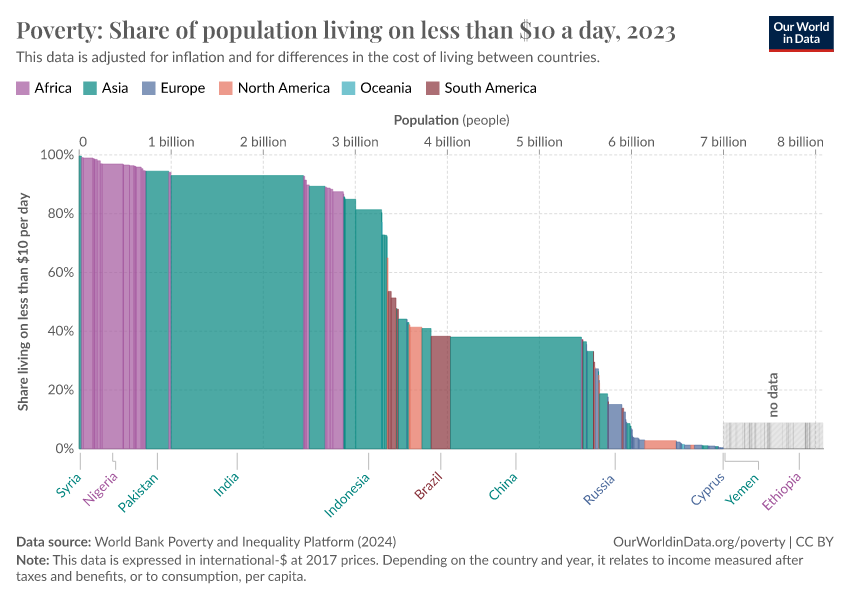

Because there is no global survey of incomes, researchers need to rely on available national surveys. Such surveys are partly designed with cross-country comparability in mind, but because they are also designed to reflect each country’s circumstances and priorities at the time of the survey, there are some important differences. In collating this survey data, the World Bank takes steps to harmonize it where possible, but comparability issues remain.

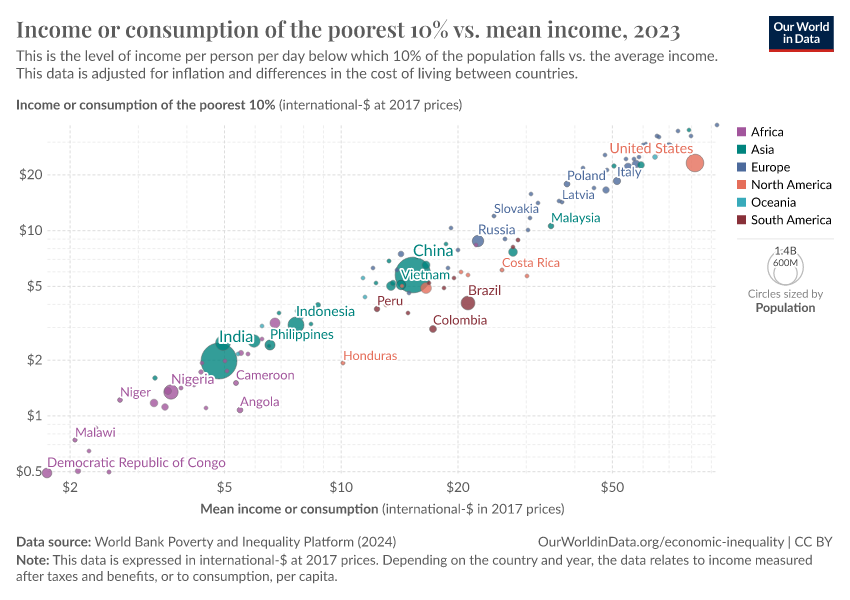

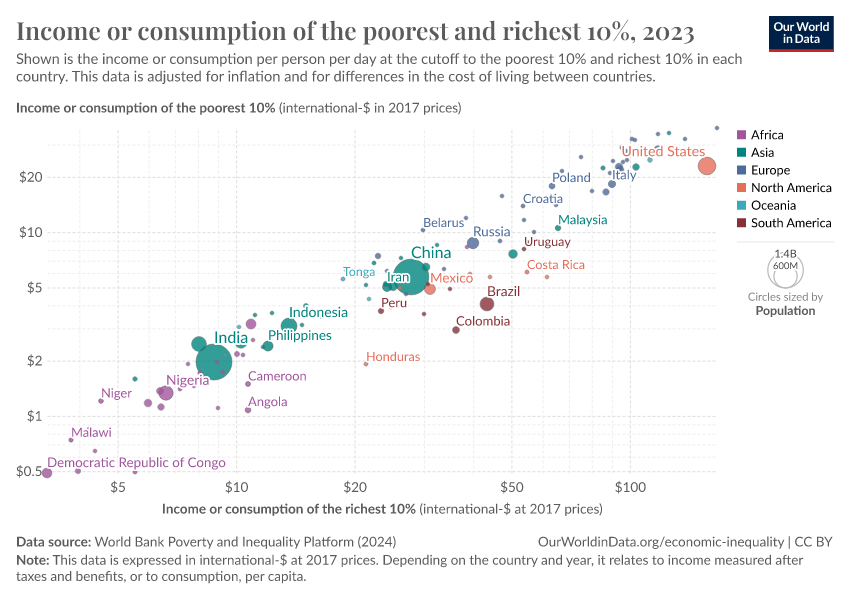

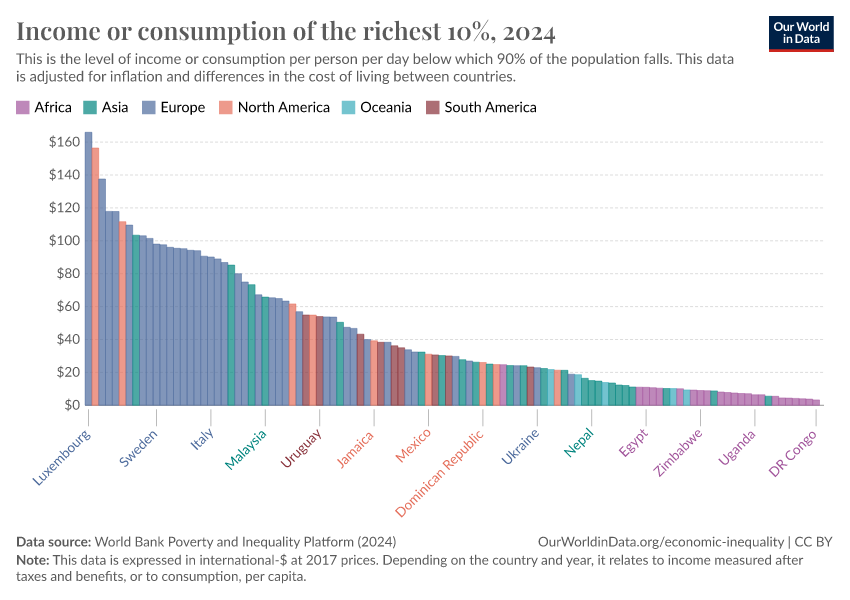

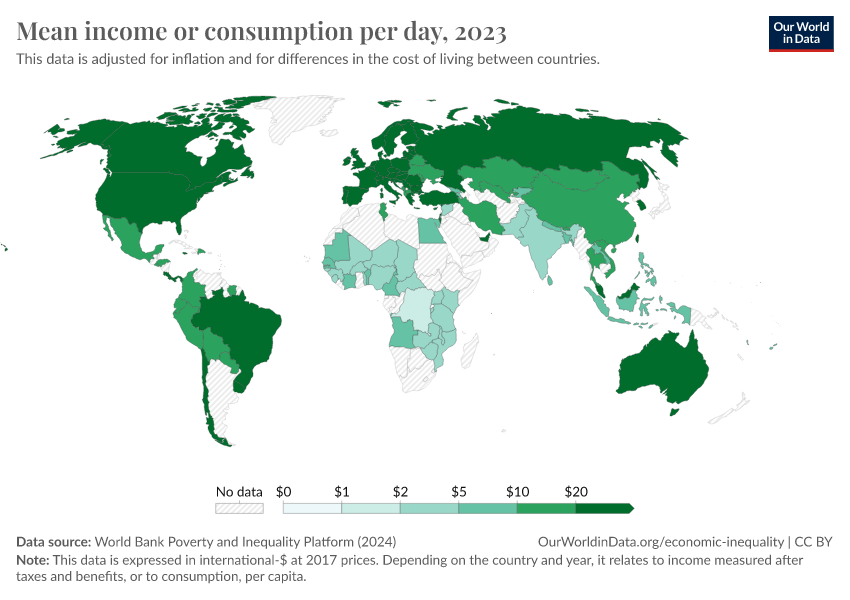

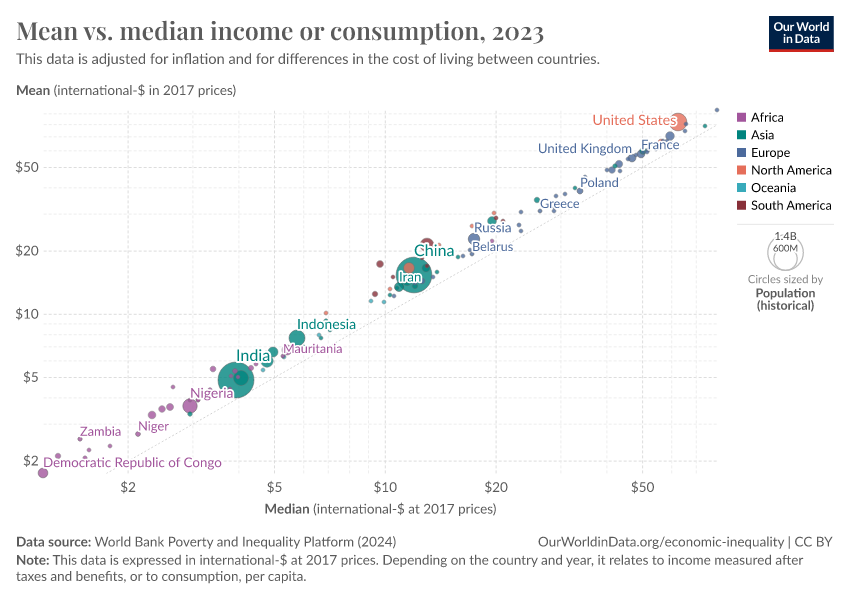

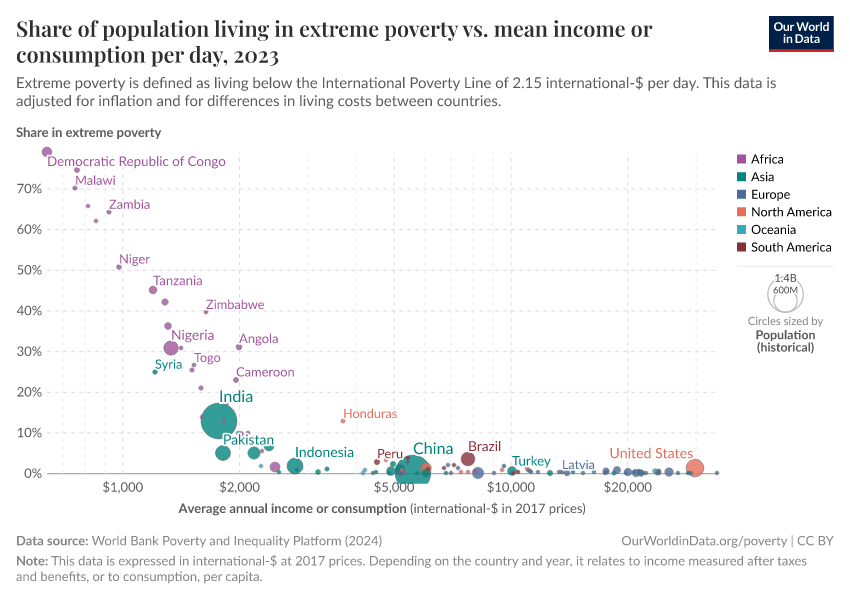

One of the most important differences is in what is being measured. The survey data included within the World Bank PIP database tends to measure people’s income in richer countries and people’s consumption expenditure in poorer countries. Countries choose the concept that can be better measured and relevant to their context. The two concepts are closely related: the income of a household equals their consumption plus any savings, or minus any borrowing or spending out of savings.

One important difference is that, while zero consumption is not a feasible value — people with zero consumption would starve — a zero income is a possible value. For instance, a person in retirement may have a very low, or even zero, income, but a high level of consumption nevertheless. This means that, at the bottom end of the distribution, income and consumption can give quite different pictures of a person’s welfare.

The gap between income and consumption is also larger at the top of this distribution. Richer households tend to save a greater share of their income, so their consumption often understates the resources they have. Taken together, one implication is that inequality measured in terms of consumption is generally somewhat lower than the inequality measured in terms of income.

In our Poverty Data Explorer, you can choose to view estimates based on only income surveys, only consumption surveys, or both types combined, which offers broader coverage.

There are a number of other ways in which comparability across surveys can be limited. The PIP Methodology Handbook provides a good summary of the comparability and data quality issues affecting this data and how it tries to address them.

In collating this survey data, the World Bank takes various steps to harmonize it where possible, but comparability issues remain. These affect comparisons both across countries and within individual countries over time.

To help users interpret changes over time, the World Bank produces a variable that groups surveys within each individual country into more comparable “spells” — periods where data is judged to be more internally consistent. Our Data Explorer allows you to view the data with these breaks in comparability indicated.

Many people in poverty today, as in the past, rely on subsistence farming rather than a monetary income gained from selling goods or their labor on the market. To take this into account and make a fair comparison of their living standards, the statisticians who produce these figures estimate the monetary value of their home production and add it to their income or consumption expenditure.

International dollars are a hypothetical currency that results from price adjustments across time and place. One international dollar is defined as having the same purchasing power as one US dollar would in the United States in a given base year. This means one int.-$ buys the same quantity of goods and services no matter where or when it is spent. You can read more about this in our article What are international dollars?.

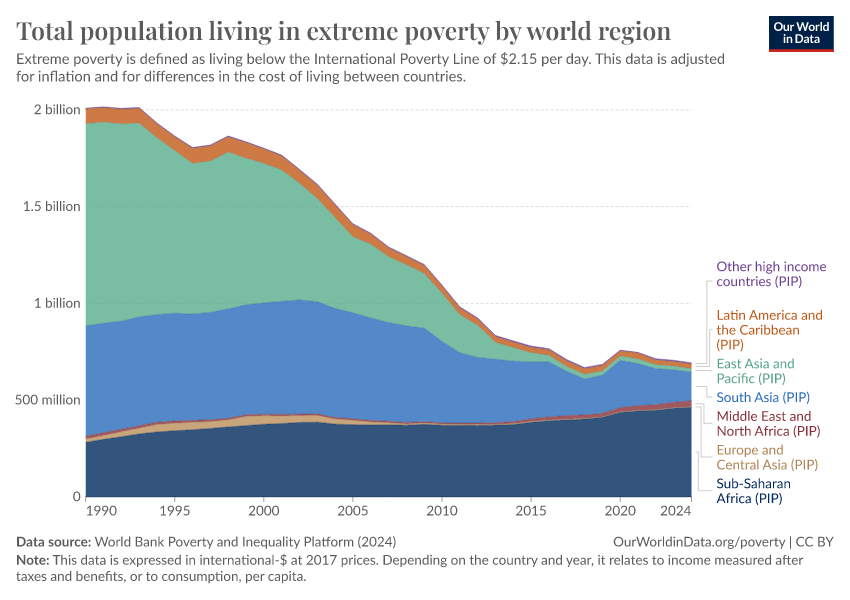

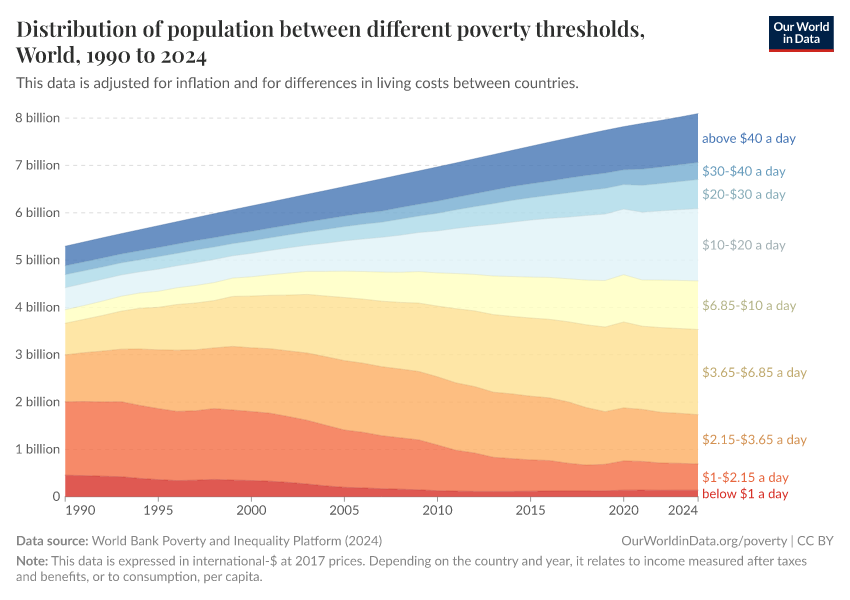

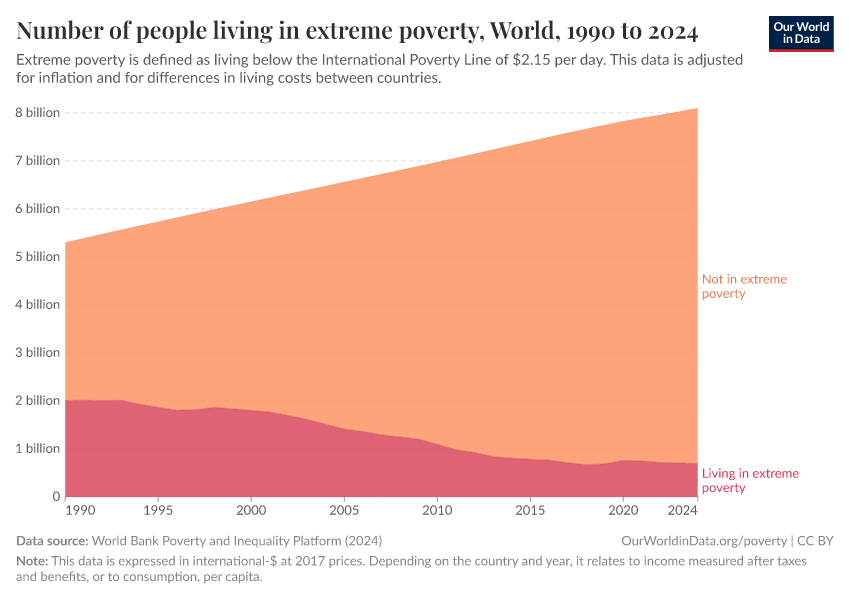

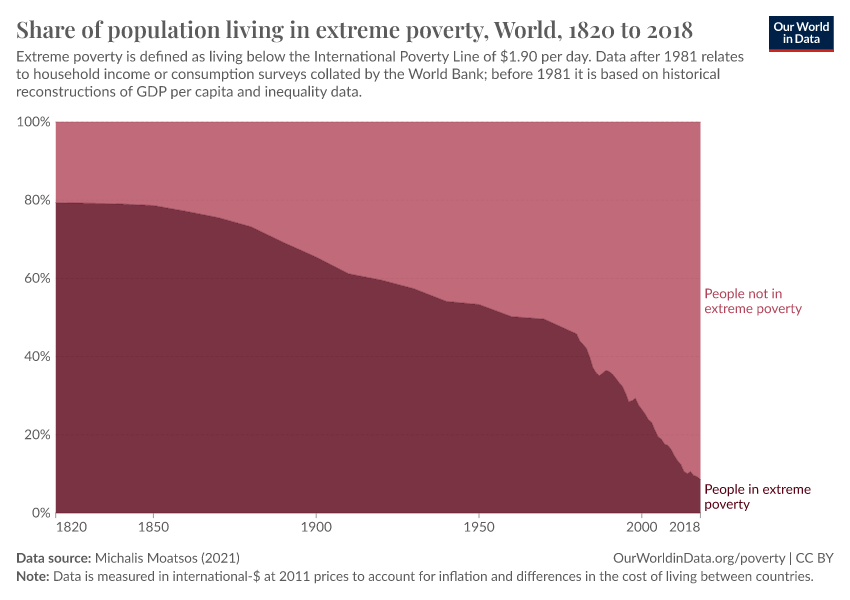

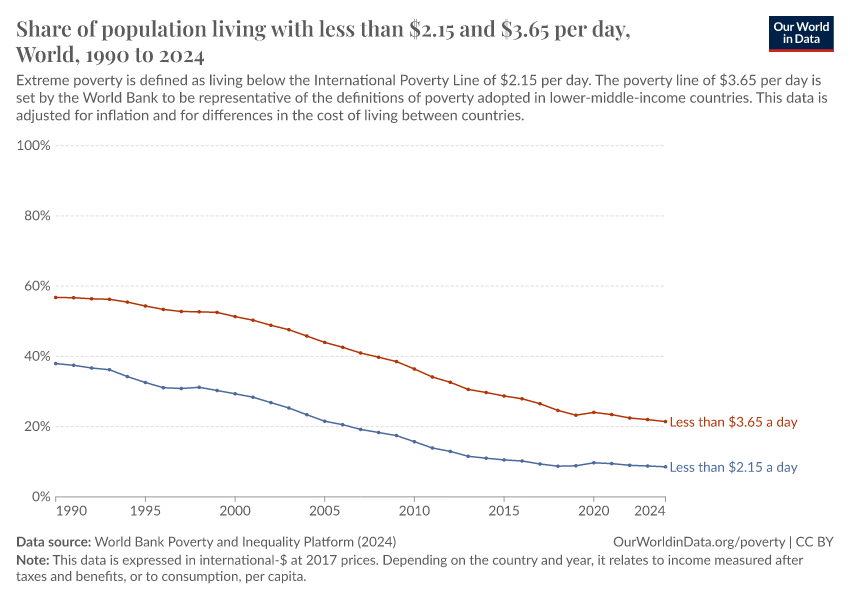

According to World Bank estimates, in 1990, there were 2.31 billion people living in extreme poverty. By 2025, that number had fallen to 808 million. The average fall over the 35 years in between is: (2.31 billion – 0.808 billion)/35 = 42.9 million. Dividing by the number of days (35 x 365) gives the average daily fall: (2.31 billion – 0.808 billion)/(35 x 365) = 118,000. (All figures rounded to 3 significant figures).

The projections are generally based on the assumption that incomes or expenditures grow in line with the growth rates observed in national accounts data. You can read more about the methods used by the World Bank in Chapter 5 of the Poverty and Inequality Platform Methodology Handbook.

The figures are taken from the data reproducibility package for the 2025 World Bank Poverty and Inequality Platform update (Lakner et al., 2025).

To generate the poverty projections for 2026 to 2030, World Bank researchers take the last observed distribution of income or consumption expenditure from household surveys and assume that it shifts in line with the projected growth in real GDP per capita from national accounts data. The GDP forecasts come from the World Bank's Macro Poverty Outlook (April 2025) and the IMF's World Economic Outlook (April 2025). The method also assumes that income inequality doesn’t change over time. You can read more about this projection method in the World Bank Poverty, Prosperity, and Planet Report 2024 (Annex 1). Lakner, C., Foster, E. M., Jolliffe, D., Ibarra, G. L., & Tetteh Baah, S. K. (2025). Reproducibility package for Global Poverty Revisited Using 2021 PPPs And New Data On Consumption. World Bank.

These figures combine data from household surveys or extrapolated values up until the year of the data release (2025) using GDP per capita growth estimates and forecasts. Projections for 2026 to 2030 are based on GDP per capita growth projections from the World Bank's Macro Poverty Outlook (April 2025) and IMF's World Economic Outlook (April 2025).

Shown are those countries with a decline of more than 30 percentage points over a period of 15 years or more. There are a number of ways in which comparability across the different household surveys on which this data is based can be limited. These affect comparisons both across countries and within individual countries over time. The World Bank’s Poverty and Inequality Platform Methodology Handbook provides a good summary of the comparability and data quality issues affecting this data and how it tries to address them. In collating this survey data, the World Bank takes various steps to harmonize it where possible, but comparability issues remain.

To help users interpret the data, the World Bank produces a variable that groups surveys within each individual country into more comparable “spells” — periods where data is judged to be more internally consistent. Our Data Explorer allows you to view the data with these breaks in comparability indicated.

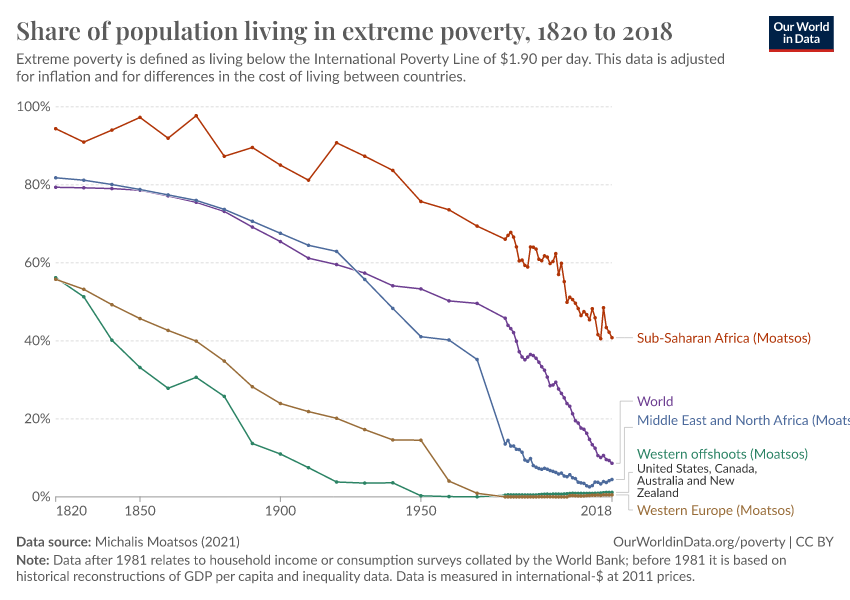

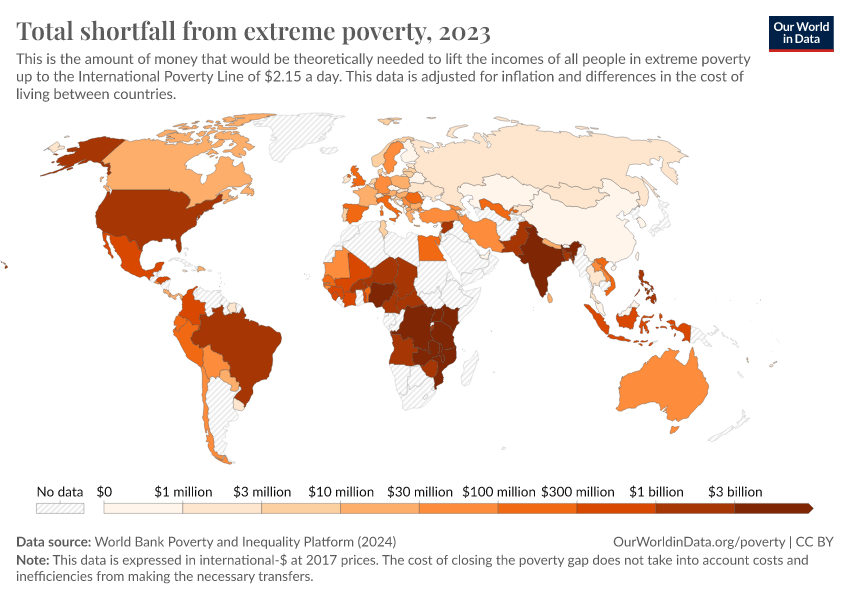

You can read more about how the International Poverty Line is used to track extreme poverty in our article From $1.90 to $2.15 a day: the updated International Poverty Line.

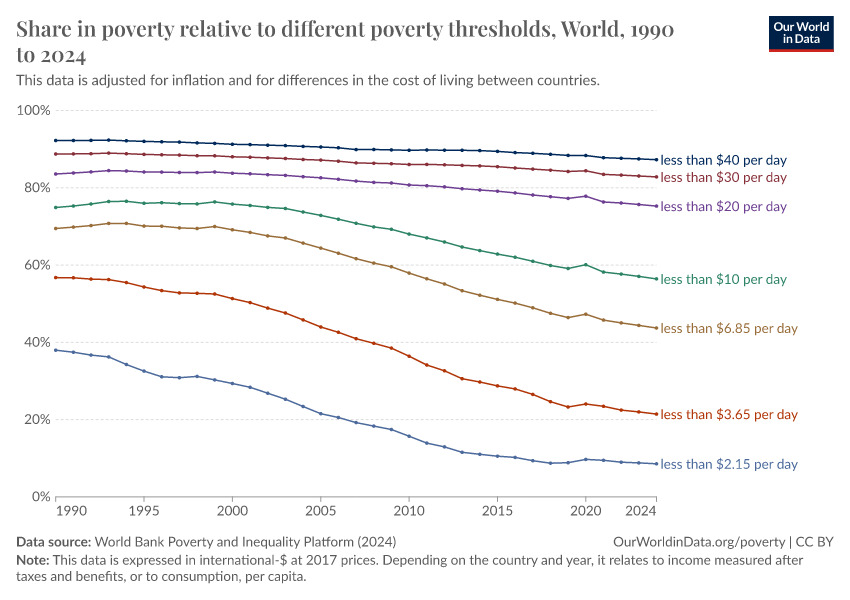

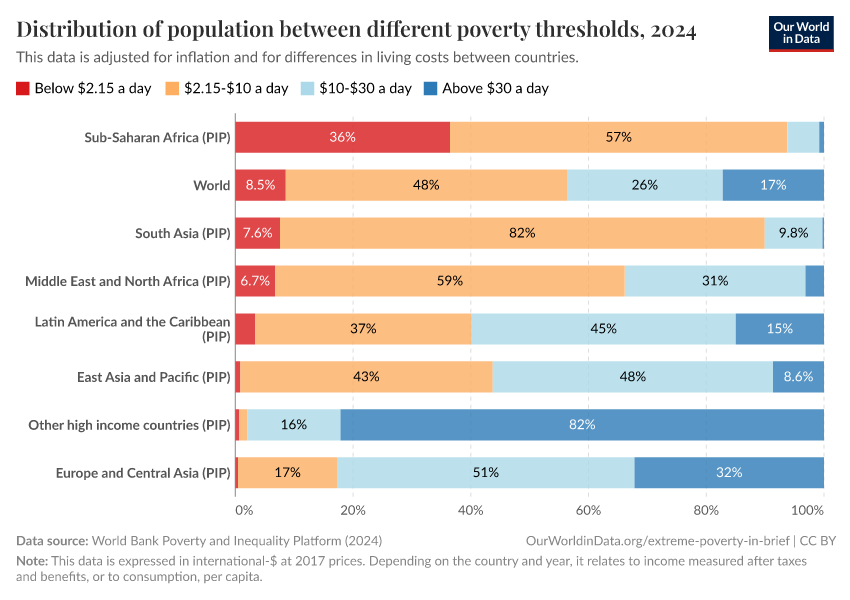

The higher line of $30 a day is broadly consistent with definitions of poverty in rich countries. See our article Global poverty in an unequal world: Who is considered poor in a rich country? And what does this mean for our understanding of global poverty?

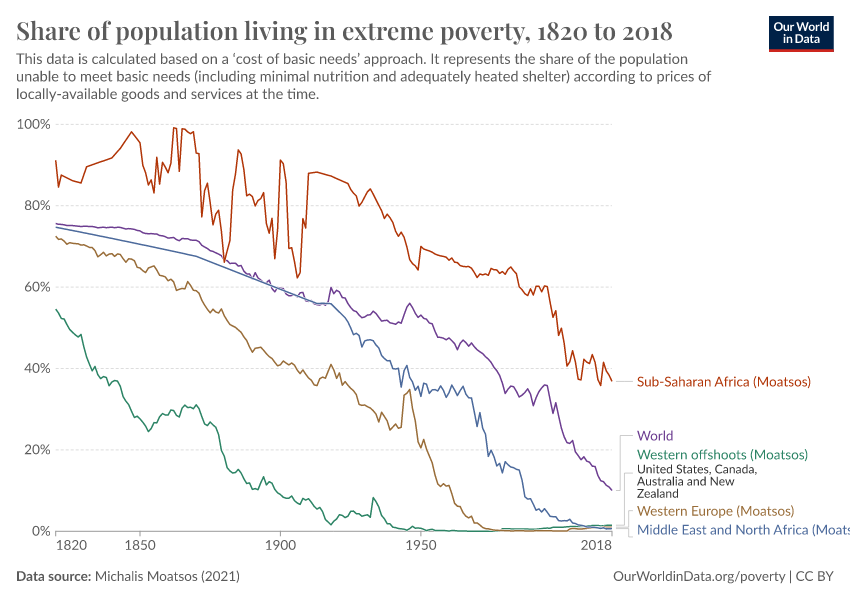

For details of the methods used to produce the long-run poverty data, see Moatsos, M. (2021). Global extreme poverty: Present and past since 1820. In van Zanden, Rijpma, Malinowski and Mira d’Ercole (eds.) How Was Life? Volume II: New Perspectives on Well-Being and Global Inequality since 1820. Available from the OECD here.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

Joe Hasell, Bertha Rohenkohl, Pablo Arriagada, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, and Max Roser (2022) - “Poverty” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/poverty' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-poverty,

author = {Joe Hasell and Bertha Rohenkohl and Pablo Arriagada and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser},

title = {Poverty},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2022},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/poverty}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.